Chris Cosentino treads where others fear to follow. He bought a Ducati Panigale V-Twin cylinder head and built a road racing Single around it. That is not an exaggeration. He built his own cylinder and bottom end for the engine, a single-shock front end, a custom swingarm and frame and all the rest.

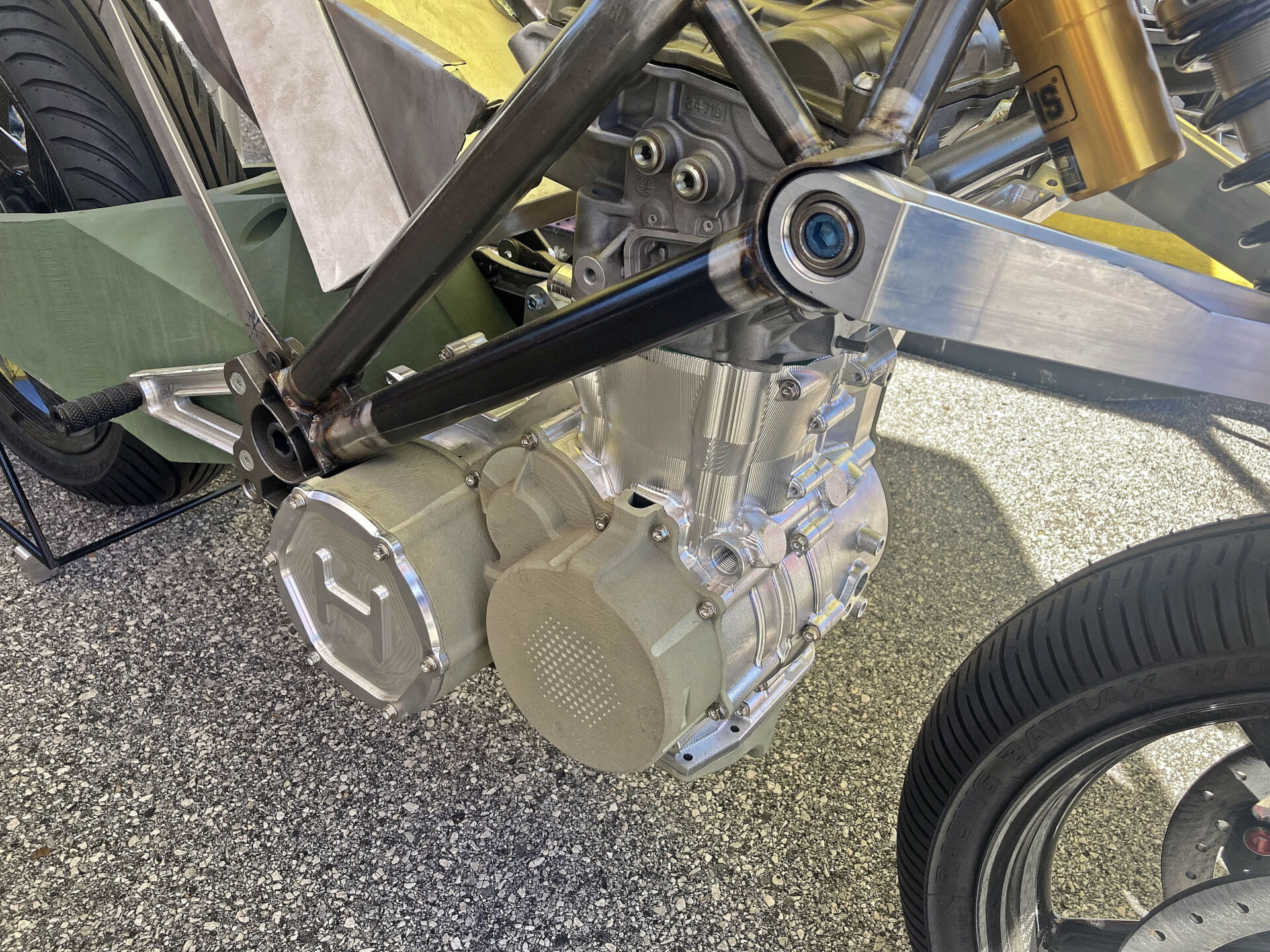

Now, with Ducati’s Hypermotard single-cylinder engine available, he and business partner Ben Claman slipped the Ducati engine into a bespoke chassis and created the Hypermono, a purpose-built racebike that their company–Cosomoto–hopes to sell in track and street configurations.

Roadracing World caught up with Cosentino at the Barber Vintage Festival at Barber Motorsports Park, where the latest prototype of the Hypermoto raced in the AHRMA Sound of Singles class, piloted by MotoAmerica racer Eli Block.

“I cut my teeth racing 125s,” Cosentino, an engineer well known for his first principles approach to racing motorcycles, says. “Once you get the taste of racing lightweight bikes, you can’t match it. So the answer was to try to make a really light motorcycle with a ton of power and brakes. That’s not really what OEMs are going for, so you start making parts, and then you realize that you’ve got to make this other part, and at some point you realize that you’re going to have to make a whole motorcycle!”

The project started several years ago. After looking at big-displacement single-cylinder engines he could buy, Cosentino purchased a cylinder head from a Panigale and carved a cylinder and bottom end from billet. The motor ran and he eventually got 60 horsepower out of it, but an engine development program strained the finances of the small company. “It was a labor of love, but engine R&D is tough, because you’re breaking expensive parts,” he says.

Impressed by the 659cc Ducati Hypermotard Single, and realizing that using an EPA-approved package would open up the possibility of selling a streetbike, Cosentino slotted the engine into his Hypermono package. For the AHRMA race, the engine still had a stock and uncracked ECU, and was stock other than the carbon-fiber dry clutch. Because the engine management system couldn’t be optimized for the non-stock airbox and pipe, Cosentino estimated that it was down on stock horsepower, but with a race ECU would be good for close to 90 horsepower.

The Hypermono’s Hossack-style front end (most motorcyclists would recognize it as similar to the Telelever single-shock front end systems found on many BMW motorcycles) features twin spars carved from billet aluminum.

“The frame and linkage are all triangulated and they are all very stiff. There’s no frame deflection like modern bikes have with their long engine hangers and the headstock moves. On this (the Hypermono), the flex is all in the uprights (fork spars).

“If I need a weaker upright with more flex laterally, I can machine a thinner-walled one and keep my bracing stiffness. The parts are easy to characterize (to predict and measure specific behaviors). I don’t have this super-complex frame that needs to be stiff in this direction and flex in this direction and all of these things. You have to do that with a bike with traditional forks. Round forks can’t bend because they seize. That’s the core of all this complicated motorcycle design. Go to a different front end design and you solve all that.”

On the other end is a swingarm that is a one-piece sand casting. The mold was 3-D printed, and the entire assembly weighs 14 pounds. In contrast, the main chassis is tubular 4130 steel. It may seem to contradict the pursuit of light weight. But when Honda gave up on its four-stroke oval-piston Grand Prix machine and created the two-stroke NS500 back in the early 1980s, the first iterations of that bike came with round steel tubes in the frame. Both Honda and Cosentino know that modifications are a necessary part of frame development in the early days, and modifying steel tubes is easier than trying to do the same with aluminum spars.

The bike currently weighs 275 pounds with fuel, Cosentino says. New carbon-fiber bodywork to replace the printed plastic and a magnesium swingarm will help get the machine down to its 255 pound (wet) target weight.

Cosomoto plans to start with a batch of 25 fully-faired track-only Hypermono machines, followed by a street version with more of the mechanicals exposed. But for now, he’s enjoying the development and honing the motorcycle in competition. And AHRMA provides the perfect environment for an engineer who is challenging design norms and wants to build the bike he wants to see.

“No one in this paddock ever asks me, why’d you do this? It’s the stupidest question to ask a motorcycle guy,” Cosentino says.