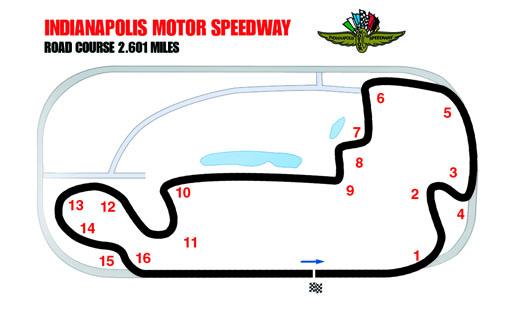

By John Ulrich It’s been 12 days since Peter Lenz crashed on the warm-up lap for a USGPRU race at Indianapolis Motor Speedway and suffered fatal injuries when he was hit by another rider, Xavier Zayat. The crash made the mainstream news worldwide, with attention focusing on that fact that Lenz was 13 and Zayat is 12. Several commentators said that kids cannot possibly control racing motorcycles or exercise the judgment needed to compete at such a young age. We heard similar claims in the mid-1980s, when the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) reacted to a surge in kids being injured and killed in All Terrain Vehicle (ATV) crashes. Early on, various government experts, self-proclaimed safety advocates and personal injury lawyers claimed that kids under the age of 16 simply cannot control motor vehicles safely. According to one newspaper story, young kids were riding 60cc Tri-Zinger Yamaha ATVs at up to 60 mph on city streets. Anybody who made and sold such “death machines” needed to be punished, and the vehicles themselves banned. One of the CPSC engineers wasn’t so sure. He had a young nephew with a dirt bike, and had spent hours watching the kid ride around with no ill effect. I was working for a company that published both motorcycle and ATV magazines at the time and I invited the engineer to come to California and watch my kids ride their ATVs, including 10-year-old Damian, seven-year-old Hayley and five-year-old Chris. We took Hayley and a CPSC delegation to Carlsbad Raceway, a local drag strip, and had her make several passes through the quarter-mile on both her Yamaha Tri-Zinger and on her bicycle. She reached a higher terminal speed on the bicycle, and didn’t break 20 mph on either of them. We then headed out to Pismo Beach, a popular riding area, with the CPSC men and all three of the kids. Hayley and Chris soon burnished an oval track in the sand and raced around in a continuation of the battles they regularly held in our back yard. Damian went exploring with several adults. Everybody survived unscathed, and the idea that kids under age 16 cannot control and ride ATVs safely took a hit. Obviously, the training the kids had undergone, the personal protective gear they wore and adult supervision they received all counted. Fast forward to 2010 and the claims we’ve all seen and heard in the media. Kids of 12 and 13 can’t possible control racing motorcycles. The track at Indianapolis Motor Speedway is too dangerous and difficult for kids. Never mind that Saturday’s USGPRU race went off without a hitch. Never mind that Peter Lenz was the first rider to die as the result of a crash in a USGPRU-sanctioned race, in the nine years that USGPRU has been in existence. And never mind that, according to CPSC data, in those same nine years, an average of 14 kids under age 15 have died annually while riding two-wheeled non-motorized scooters, the aluminum ones that combine a deck and a handle and that a kid rides by standing with one foot on the deck and pushing with the other foot. Some of the talking heads on TV seemed to think that anybody and everybody racing at Indy is running on the famous oval, and that the USGPRU kids were flying around the oval nose-to-tail at 120 mph. Motorcycle races actually run on the 2.6-mile road course, which combines the front straightaway and a short section of oval-track banking with a series of left and right turns. Peter Lenz crashed exiting one of the slowest corners on the track, Turn Four, during the warm-up lap for the Sunday USGPRU race at Indy. Turn Four of the road course is a left-hander that sends the riders onto a short section of oval-track banking located between oval-course Turns One and Two. To keep riders pointed away from the wall on the outside of the oval course as they exit Turn Four, track workers installed removable metal curbing on rider’s right. The metal curbing is coated with anti-skid grip paint and offers good traction. By nature, riders are not up to racing speed on the warm-up lap, particularly not by the fourth of 16 turns on a road course. By the time he reached Turn Four, Peter was third in the string of 24 young riders on the warm-up lap, ahead of fellow USGPRU racer Stefano Mesa, age 16. The way Stefano tells it, as Peter exited the corner, he drifted high and got onto the metal curbing, losing the front and low-siding, the bike falling on its left side and immediately shooting off to the left and out of the way. But Stefano says that Peter landed on his butt and slid along the track in the same direction as he was originally headed, sitting upright and waving his hands over his head to warn other riders as he rotated around and around. Stefano missed Peter on the inside and continued on his way but soon slowed as officials threw the red flag. Stefano’s account of the start of the fatal crash coincides with what USGPRU President Stu Aitken-Cade said he saw on video of the incident captured by the track’s camera system, which monitors and records everything that happens in every corner. According to Aitken-Cade, while Peter spun down the track sitting up, waving and slowly coming to a halt, about 10 riders passed him. Then there was a gap in traffic and Peter started to stand up. At that moment, a group of three more riders exited the turn. The first two riders were in line, rear wheel to front wheel. The third rider, Xavier Zayat, was slightly behind, inside and to the left of the other two, his view of Peter blocked. As fate would have it, the two riders immediately ahead of Xavier slowed slightly and Xavier popped out to the right to pass them on the outside. While the two riders ahead of Xavier narrowly missed Peter and passed him on the inside on rider’s left, Xavier suddenly found himself confronting a windshield full of half-standing Peter. There was no time and no space for Xavier to do anything, and in the next millisecond Xavier hit Peter, Xavier and his bike both tumbling down the track. First responders attempted to restart Peter’s heart with CPR and transported him to the local hospital while the rest of the riders–minus Xavier–waited for another warm-up lap and the start of the race. The race was over and I was standing with now-adult Hayley in the USGPRU pit area when I received a text message from Michael Lenz, Peter’s father, who was at the hospital. The text message read simply, “Peter passed away.” Ed Sorbo rushed up to me holding his cell phone, having just found out himself. Another text message from Michael Lenz followed, revealing that Peter had suffered a broken neck. As the news spread through the pits, Xavier sat in a chair, bent over with his face on his knees and his arms wrapped around his head, sobbing. (Earlier, Hayley and I had watched and listened in horror as Xavier’s father, after hearing about the crash, had screamed at Xavier, “YOU HIT THE PERSON?! YOU HIT THE PERSON?!”) The other USGPRU racers gathered and talked about Peter, holding in effect their own impromptu memorial service. And then the news blitz began, complete with an attorney suggesting that Peter’s parents be prosecuted for child endangerment because they allowed their son to race motorcycles. The death of Peter Lenz is tragic, as is the death of any child. To the people who knew Peter, it doesn’t matter that kids die every day for a multitude of reasons. To the people who knew Peter, it doesn’t matter that in the nine years that USGPRU has been in existence, more than 100 kids under the age of 15 have died riding non-motorized scooters, without any lawyers suggesting that their parents be prosecuted for allowing their kids to ride such a dangerous device. Other kids, including Stefano, had ridden on the metal curbing before Peter’s crash, without problem. Exactly why Peter crashed at that place and at that time is impossible to determine, although he may have gotten too high on the curbing and clipped a lip at the top of each metal section that may be in place to discourage riders from jumping over the curb itself. The bikes were not at full speed, the riders grabbing fourth gear as they exited the corner at what Stefano estimated to be between 50 and 70 mph. And there’s no magic age that solves the problem of being the third rider in a line of three with your vision blocked as you come up on a crash scene or other problem. This type of crash, although thankfully relatively rare, can happen on a straightaway, when three riders in a drafting line come up on a fourth rider who has slowed suddenly with a mechanical problem, the first two riders splitting left and right and the third rider in the line–their forward view blocked–running straight into the back of the slowing rider. I saw that happen in the 1970s, involving adult riders, at Ontario Motor Speedway. It can also happen in a corner, as seen in a famous video shot in the 2000s at what was then called New Hampshire International Speedway. A group of three adult riders came into a turn where cornerworkers were removing a crashed bike; the first two missed the workers and the third rider–his view blocked–hit one of the workers, who was seriously injured. (The only good thing that came out of that fiasco was LRRS race officials reverting to the industry standard of throwing a red flag and getting all the riders and bikes off the track before sending workers out onto the racing surface.) Clearly, what happened at Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Sunday, August 29th, had nothing to do with the age of the participants, the speed of the machines, or the race course itself. Having said that, spare a thought for the Lenz family and for Peter’s parents, who are living every parent’s worst nightmare. And also spare a thought for young Xavier Zayat, the kid who couldn’t see Peter until it was too late, with no time and no space to avoid hitting him. (To be continued…)

FIRST PERSON/OPINION: Peter Lenz, Xavier Zayat And The Day It All Went Wrong At Indy

FIRST PERSON/OPINION: Peter Lenz, Xavier Zayat And The Day It All Went Wrong At Indy

© 2010, Roadracing World Publishing, Inc.