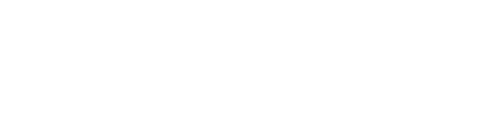

Editorial Note: This article was originally published in the March 2018 print issue of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology.

2018 Sportbike Intro: Ducati Panigale V4 S

Dawn Of The New Ultra-Performance Era

By Chris Ulrich

I could see a rider off in

the distance as I took the checkered flag at the end of my first racetrack

session of the day on the newest Ducati sportbike. Not wanting to give away

valuable testing time by touring, I stayed on the gas, pushing hard through

Valencia’s

fast third-gear left-hand Turn One, which is taken at well over 150 kph (over

90 mph). It’s

a daunting piece of racetrack that was forever etched into MotoGP history when

Marc Marquez famously saved his 2017 World Championship title there, losing the

front but keeping the bike upright on his knee!

Exiting the turn, I kept

pushing in the run to Turn Two, a relatively slow, second-gear corner. I got on

the brakes late, still careful to not rush the entry, rotated the Panigale V4 S

and fired it out with the DTC (Ducati Traction Control) and DWC (Ducati Wheelie

Control) indicators lighting up the dash.

I drew closer to the rider

ahead, and could see that he was slender and wearing slightly baggy leathers,

and reminded myself to stay on task. The V4 and I railed through the fast,

left-hand Turn Three and then headed toward the first right-hand turn on the

Valencia road course, Turn Four. I knew the tires were hot, but the ambient

temperature was cool, so I was a little careful on turn-in but was back on full

gas exiting and driving into Turn Five—another right-hand turn taken in second

gear—trailing off the brakes, the ABS barely kicking in. Hitting a late apex, I

clipped the inside curb late and opened the gas as the rear tire of the

Panigale dug in, the carcass flexing and the tire spinning slightly as the DTC

kicked in and helped the Pirelli Supercorsa SP regain enough traction to

flatten the contact patch and drive the bike forward, setting off a slight

wallow as I headed to Turn Six.

I lit the rear tire up and

ripped through the gears as I headed out of Turn Six and through the

back-straight kick, which doubles as Turn Seven, and slammed on the brakes for

Turn Eight. The rider ahead of me was larger, and I could make out the colors

of a Ducati Factory suit with the numbers 00 emblazoned on the center of the

back—and he wasn’t touring, either. The fun of making a pass never gets old; you can take

the racer out of the race, but you can’t take the race out of the racer. Through the

Turn Nine left-hand kink now, then back to the right for Turn 10 and into Turn

11, a 180-degree right. I trailed the brakes out to three-quarter track width,

then released them and rolled through the middle of the corner before

tightening my line; the Panigale V4 turned down nicely, allowing me to clip the

inside curb and open up the exit for maximum drive, and now I had just a few

more meters to close before I was within a safe striking distance for making a

pass.

(Above) Chris Ulrich (right) with Ducati CEO Claudio Domenicali (left) on pit lane at Valencia.

I closed up more as I

braked late for Turn 12, a short, right-hand flick. Then I whipped the bike

from right to left and slammed it on my knee, pulling the throttle back to the

stop and flying around the outside of the rider I had been chasing. The rear

tire protested and I was well into the DTC followed by the DSC (Ducati Slide

Control) with the rear tire searching for grip. I stayed on the gas as I

crested a hill and spotted the final turn, before rolling off, signaling and

putting on the brakes. As we headed into pit lane, I realized the rider I’d chased down and gone by

well closer than necessary was Ducati CEO Claudio Domenicali. Thankfully it was

all smiles when we took our helmets off on pit lane.

***

When the motorcycle

industry is struggling to find its way and reach new riders, it is impressive

to see the CEO of Ducati going fast on the racetrack and enjoying the

motorcycles the iconic company sells. Domenicali is a CEO who is more in touch

with the passion of motorcycling than most top executives in the motorcycle

business, saying, “We have to always remember what we are existing for, as a brand, as a

company, as a group of people. It’s very, very important to come back to reality,

and remember what two-wheel emotion is about.”

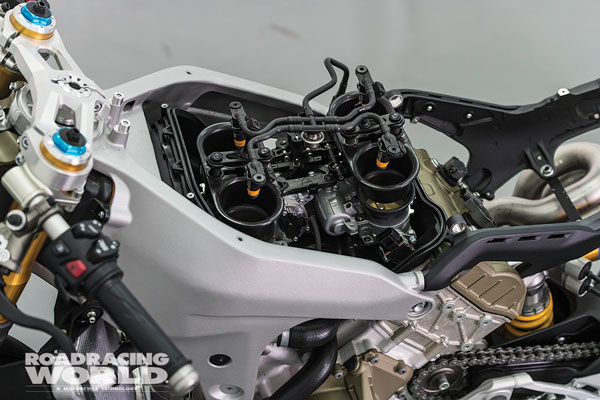

(Above) The Ducati Panigale V4 S without bodywork, showing the cast aluminum-alloy main frame and magnesium sub-frame, which both bolt to the engine.

That two-wheel emotion at

Valencia was about a MotoGP-derived V4 production street motorcycle with a

claimed 214 horsepower that happily does power-slides and power-wheelies, and

marks a new era for Ducati. The Italian company has built a streetbike that put

an ear-to-ear grin on the face of every member of the very seasoned group of

motojournalists gathered at Valencia for the official worldwide press intro.

The V4 era at Ducati is all about big passion, combined with big

performance. And that passion starts at

the top with Mr. Domenicali.

(Above) The Ducati Panigale V4 S with bodywork, posing at the racetrack.

Being in touch with the

emotions and sensations generated by motorcycling could explain why Ducati’s worldwide sales have

continued to grow. Granted, the brand’s U.S. sales grew just a little over 1%, but

hey, it’s

growth at a time when some companies are dealing with declining or flat sales.

In my opinion, Ducati’s corporate passion is a big part of the company’s success, along with a willingness to

continually build cutting-edge machinery without compromise. In regard to the

Panigale V4, Ducati abandoned the engine configuration that made the brand and

moved on without fear of the next challenge. And Ducati engineers then

designed, developed and built the fastest and most advanced street motorcycle

that has come to market this decade. And the company as a whole is unapologetic

about the big decision to build a four-cylinder flagship. That being said, fans

of V-Twins shouldn’t worry—Ducati will keep using the V-Twin configuration for models below

1000cc.

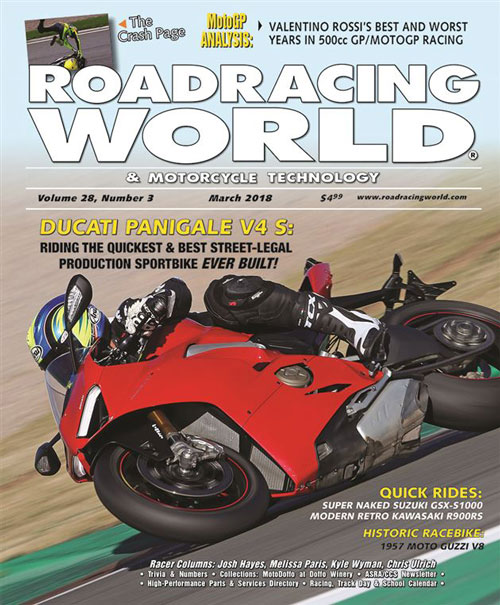

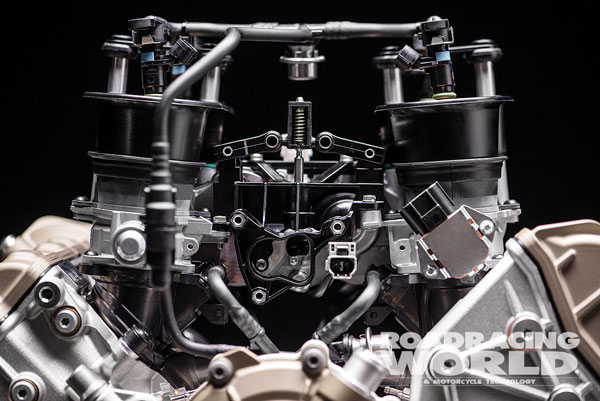

(Above) The Desmosedici Stradale V4 engine with Mikuni fuel injection throttle bodies in place.

Still, some die-hard

Ducatisti may say the latest Panigale and its Desmosedici Stradale V4 engine is

not a representation of Ducati and disrespects the brand’s V-Twin heritage, and that it’s heresy for Ducati to

build anything other than a street-legal, V-Twin four-stroke sportbike. But

Ducati’s

roots are in racing and building high-performance motorcycles that can win road

races at the highest level of competition. The Panigale V4 may be a new

direction, but it does not abandon Ducati’s roots, it embodies the company’s tradition of building

technologically advanced, high-performance motorcycles. Make no mistake: The

2018 Ducati Panigale V4 is all about performance. It is also packed with

technology, and is a fitting machine to lead Ducati’s line of performance-oriented sportbikes well

into the future.

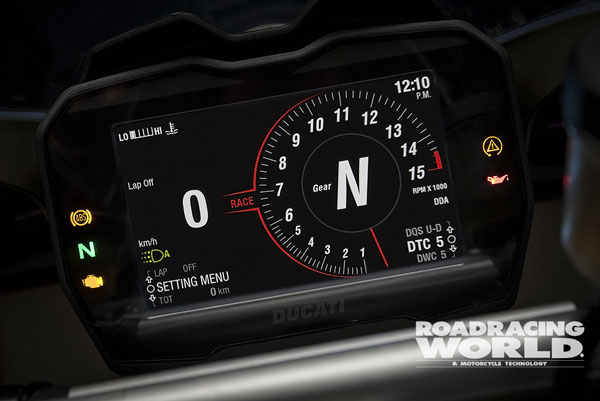

(Above) The Ducati Panigale V4 S has the best electronics available on a production sportbike sold to the public, including adjustable Ducati Traction Control (DTC), Ducati Wheelie Control (DWC) and Ducati Slide Control (DSC).

Let’s

face it, the Panigale 1299 and the preceding over-1000cc V-Twin Panigale models

could be very difficult to ride around a racetrack at speed. They demanded a

high level of skill, absolute concentration, and top-notch fitness to push

anywhere near the limits of the bike. The big V-Twin Panigales could also be

hard to understand, which made setting the bike up to be competitive at

different racetracks more complicated than it was with other bikes. The

demanding nature of the V-Twin Panigale showed in its results on the racetrack:

It took Ducati two seasons to win its first Superbike World Championship race

with the Panigale 1199 R and the bike never produced the type of consistent

racing success enjoyed with the steel-tube trellis-framed 851, 888, 916, 999,

and 1098-based Superbikes. (We could also list assorted subsets and

developments of those original models, but it would be moot. You get the point…)

(Above) View from above the cast aluminum-alloy main frame and magnesium subframe bolted to the engine, and the double-barrel throttle bodies with variable length velocity stacks mounted above and between the cylinder banks.

This could be due to the

1199 R’s

monocoque chassis design or the extreme dimensions of the Supersquadro V-Twin

engine or a combination of both. Imagine the gyroscopic effect set off by the 1199 R’s two-massive 112 mm pistons (116 mm for the

1299 R, which is too big for World Superbike rules), located relatively high in

the chassis, banging around inside the engine and spinning the crankshaft at

very high rpm. The bottom line is that the racebike was a beast and Ducati

needed a big change to tame it.

Solidifying the decision was the fact that

Ducati engineers realized they would have to go to beyond 1299cc (the

displacement of the latest Panigale 1299 R streetbike) to make the Panigale the

most powerful production sportbike on the market. So they took the next logical

step, building a V4 powered sportbike using technology from Ducati’s title-contending

MotoGP program.

***

Ducati could have played it

safe for the international press introduction of the Panigale V4 S and gone to

a more forgiving track than the Ricardo Tormo Circuit in Valencia, Spain. The

track is relatively tight with only one real straightaway to rest on, which makes

it pretty physically demanding even if you are race-fit. That means it’s a total ball-buster if

you are a desk-bound journalist, but I’ll leave the subject of my non-racing fitness

level for a column! Ducati marketeers and engineers wanted a track where the

Panigale V4 could show off its handling prowess while highlighting the

strengths of both the engine and the electronics package, proving the new

flagship model to be the total package. So they chose Valencia as the ideal

location to do it.

(Above) Chris Ulrich gets ready to square-up a corner at Valencia on the 2018 Ducati Panigale V4 S. The Ducati Slide Control (DSC) system allows the rider to drift the rear wheel to rotate the bike mid-corner.

In terms of ergonomics, the

Panigale V4 S feels very similar to its V-Twin predecessors. The seat position

is aggressive, the reach to the handlebars long, the fuel tank narrow, and the

footpegs high—10 mm higher than the pegs on the 1299 R. Thanks to an uneven

firing order, the V4 sounds slightly like a V-Twin while idling. In fact, the

power delivery feels slightly like a V-Twin out on the racetrack, too.

The Panigale V4 S didn’t disappoint at all on

the racetrack, even during the first orientation session when the electronics

were set in the less-aggressive Sport Mode, which slightly softens the throttle

map and the power delivery. At the start of the intro, the rider aid settings

were also turned up with DTC on 5, DWC on 4, DSC on 2 and ABS on 2. Even with

the softer throttle map and the rider aids turned up, the Stradale engine was

impressive from the first exit of pit lane. And the electronics intervened very

smoothly. It felt like power reduction is handled by reducing the rate at which

the throttle plates open, depending on the mode selected and the lean angle;

the abrupt power cuts experienced on the big Panigale V-Twin models are gone.

My first impression of the

chassis was also positive. It isn’t overly stiff, and the Panigale V4 turned in

well, rotated well at the apex, then finished the turn without pushing wide.

And it was much easier to close my line in Valencia’s long, 180-degree turns like right-hand Turn

11. I could carry good speed at corner entry, which forced the bike to the

middle of the track, then rotate around

at three-quarters of the way through the turn and get back down to the inside

curb, which put me in position for a great drive at the corner exit. I would

have been plowing the front tire and cursing if I had tried to do that at the

same entry speed on the old bike. The new, more balanced handling

characteristics are helped by the counter-rotating crankshaft, which helps

reduce the gyroscopic forces created by the wheels. In my first 10 minutes of

riding the Panigale V4 S, I could already tell that the Ducati engineers had

done something special.

Once that first orientation

session was over, technicians set the electronics in Race Mode for the

remainder of the sessions. That change delivered more direct throttle

opening—it feels like it’s 1:1—and

unleashed the full power of the Desmosedici Stradale engine. The techs also

dialed-in slightly more aggressive rider aid settings of DTC 3 and ABS 1. I

took it a step further as the day went on, turning the rider aids down in each

session before finally landing on DTC 1, DWC 2, DSC 1, and ABS 1.

In Race Mode, power starts

to build from around 7,500 rpm and the bike continues to pull hard until around

13,500 rpm. The Ducati feels like it really takes off as the revs climb over

11,000 on the straight, and I suspect this is a by-product of the constantly

adjusting variable-length intake track going from long to short funnels.

(Above) The double-barrel Mikuni 52mm throttle bodies are seen here with the variable-length velocity stacks in the closed, long position for better low-range power and acceleration. At about 11,000 rpm the upper section lifts off and opens shorter lower stacks for increased top-end performance.

Power was impressive when

accelerating, but it wasn’t too much to handle, even with the DTC and DSC turned down. The linear,

controllable power delivery is a product of what Ducati calls its

“twin-pulse” uneven firing order: The cylinders on the left side fire

at 0 and 90 degrees of crank rotation, followed by a 200-degree pause before

the cylinders on the right side fire at 290 and 380 degrees, which is why the

V4’s power

delivery feels similar to a V-Twin’s power delivery. The relatively long gap

between power pulses gives the rear tire time to recover traction before the

next power pulse hits. The result is smooth power from initial throttle opening

through the acceleration zone. The Stradale engine delivers strong, tractable

power throughout the rev range, and also has a high rev limit to produce top

speed.

The electronics obviously

contribute to the smooth, controllable power delivery without any

abruptness—especially at initial throttle opening—no matter what mode or DTC

setting is selected. What it all meant was that I could crack the throttle and

start my drive without having to think about being delicate when going back to

the throttle after the part of the corner when you’re between trail-braking and initiating

throttle.

(Above) The Panigale V4 S TFT dash has what looks like an analog tach.

In terms of function, the

Ducati Traction Control (DTC), Ducati Wheelie Control (DWC), and Ducati Slide

Control (DSC) were solid. All three systems helped keep the Panigale V4 moving

forward through the acceleration zone without abruptly removing power. The DTC

would gently remove power from full lean to about three-quarters of the way

through the corner, then the slide control would take over, then the wheelie

control would come in as needed.

Ducati Slide Control is new

and makes you feel like a hero once you wrap your head around it. On most laps,

I’d get into

the DSC exiting Turn Six. The system allowed me to light up the rear tire and

drift out to the exit curb without letting off the throttle, the DTC and DSC

indicator lights on the dash lit up the whole time. But the slide control didn’t hold the bike back when

engaged; instead, it balanced the grip-to-slide ratio to keep the Ducati

Panigale V4 constantly driving forward.

(Above) A diagram of how the tank fits over and behind the airbox and extends down and under the seat, to carry the weight of the fuel lower.

The Panigale V4 S chassis

was as impressive as the engine and electronics were. The new cast

aluminum-alloy frame with an attached magnesium subframe is stiffer and

provides a more direct feeling during turn-in and while transitioning the V4 S.

The frame had none of the twist, pump, twist experience common on the 1299

model. It was user-friendly from the start of the day until the end, whether I

was pushing or cruising around while playing with settings.

The fact is that I didn’t have to ask for many

changes to the chassis during the day, highlighting the improvements Ducati

engineers have made to the balance of the Panigale V4 S when compared to the

1299. It also responded as expected to suspension changes. The Öhlins Smart E.C. suspension

can be tuned for specific parts of a corner, with software dividing cornering

performance into three zones: Brake Support, Mid-Corner, and Acceleration. I

wanted more support on corner exits at Valencia, so I made an Acceleration zone

change (going from Level 2 to Level 4, which increased rear shock compression

damping) to give the Panigale V4 more

rear support. The change made the bike finish the corner better, but with

slightly less grip, which gave it more linear slide characteristics during

acceleration.

What was most impressive

was the fact that the change only affected the bike in the Acceleration

zone—the exit phase of the corner, from the end of the apex to the actual exit.

It was amazing to be able to change the bike’s behavior in a specific area of the corner,

without affecting any other section of the corner. The end result was a more

comfortable rider who turned faster lap times. Everything that happened made

sense.

I’ve

never been a big fan of ABS on motorcycles, but the new Bosch Cornering ABS EVO

system used on the Panigale V4 is really impressive. Set-up 1 is minimally

intrusive and allowed aggressive initial braking along with trail-braking down

to the apex without any apparent reduction of brake feel or power. The system

performed very well, allowing me to brake how I wanted, without intervening by

reducing braking power and causing the bike to run wide. The system also allows

the rider to slide the rear wheel and back in the bike when Set-up 2 is

selected. Frankly, backing the bike in is either specific to a rider’s style (and is usually a

slower way around the track) or a by-product of speed combined with poor clutch

or ECU set-up. And because I rarely use the rear brake, the ability to back it

into corners with the bike at 0-35 degrees off vertical did not really impress

me.

But staying on the subject

of electronic aids for braking, the Ducati Quick Shift (DQS) EVO worked and

Engine Brake Control (EBC) EVO helped keep the Panigale V4 S in line while

entering the corner. The duration and rev spike of the auto-blip function was

just right to provide smooth, clutchless downshifts without making the

transmission clunk into gear or pushing the bike into the corner. But I felt

the EBC had a little too much run-on, too early when braking hard for a corner,

even when set on Level 1, which is the maximum amount of engine braking

available. Once I had finished braking hard and was into the corner, the

lean-angle-dependent engine braking strategy provided the right amount of

engine brake to keep the wheels inline, dragging the bike down so I could

rotate it around the apex.

In an effort to find a

setting I was more comfortable with, I turned the EBC off completely for a few

laps during the session (I had to be stationary in the pit to turn it off). On

track, the Panigale was then better during hard braking, slowing down nicely,

but then there was too much engine braking once I got to the apex of the

corner—I had to crack the throttle early and get the engine going so I could

roll through the corner. In the end, I went back to EBC 1 and instead increased

my initial brake pressure.

To demonstrate the

performance of an uncorked Desmosedici Stradale V4 engine, Ducati sent

journalists out for one final session late in the day, aboard a modified Panigale

V4 S. The bike made 12 more horsepower than in standard trim, thanks to a

titanium Akrapovic racing exhaust system and revised engine mapping; had

revised DTC and DWC strategies; and was fitted with Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa

Pro slicks to handle the extra power. Ducati reps claimed the modified bike

made 226 horsepower at the crank and it only took one gear shift after my first

exit from pit lane to make me a believer! The modified Panigale V4 S pulled

harder than any of my Superbikes ever did and just kept going with no end to

the power. I’m

usually a less-is-more type of guy when it comes to electronics, but the

Panigale V4 S with the Akrapovic system made me regret my decision to turn down

the electronics before riding the bike! I tried to be conservative and waited

until the exit of Turn Six coming onto the back straight before I really

grabbed a handful of throttle. The front wheel was immediately off the ground

with the rear wheel lit up at the same time!

But the modified bike was

still a lot of fun to ride. Nothing brings out chassis problems like more

horsepower and grip, but the Panigale V4 was up to the challenge, and I found

myself cranking the V4 over and dragging my toes and boots more than usual

during my 15-minute final stint.

Ending the day ripping laps

on a hopped-up version of the Panigale V4 S drove home the fact that Ducati

motorcycles—at least since the first one I tested, the 998R—are all about

performance. And the company is willing to do what it needs to build the

best-performing, most-cutting-edge sportbike on the market, even if that means

abandoning the engine formula that it built its name on. I predict that the

Ducati Panigale V4 S not only marks the start of a new era for the brand, but

will also set the bar for ultra-performance sportbikes for years to come.

Tech Details

Motorcycles are becoming,

lighter, smaller, more compact, and more powerful than ever to gain an

incremental advantage on the competition. Small things count more than ever

these days, and what look like small details on paper can translate into big

lap time gains on the racetrack. The Panigale V4 is all about the details, from

the engine to chassis. The Panigale V4 S I tested in Valencia puts out a

claimed 214 horsepower at the crank and weighs in at 430 pounds (195 kg) wet,

which gives it a power-to-weight ratio of 1.10 horsepower per pound. The

Panigale V4 is oozing with real MotoGP technology, not just a fairing, but

rather real-deal hard parts including the engine configuration, bore diameter,

Desmodromic valve actuation, firing order, and the crown jewel of its enhanced

performance, a counter-rotating crankshaft.

(Above) The Ducati Panigale V4 S crankpins are offset by 70 degrees to create what Ducati calls its “twin-pulse” uneven firing order, for better traction.

We’ll start with the

90-degree V-4, 16-valve Desmosedici Stradale engine. Ducati engineers leaned

heavily on the company’s MotoGP program for direction on the engine, and used the same bore, 81

mm—the maximum allowed by MotoGP rules. Because the first Panigale V4 was

going to be sold as a streetbike, the engineers increased the displacement from

MotoGP’s

maximum of 1000cc to 1103cc by using a longer, 53.5 mm stroke to maximize

torque output and create a nice, linear powerband. The compression ratio is a

very stout 14.1:1.

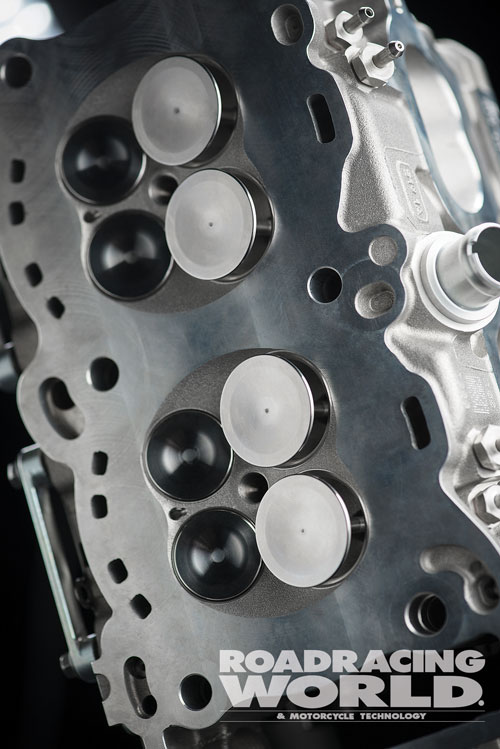

(Above) The Stradale engine’s 81 mm pistons are precisely shaped to produce a 14.1:1 compression ratio.

Probably the coolest and

most effective MotoGP feature is that counter-rotating crankshaft. Spinning the crank in the opposite direction

of the wheels helps negate some of the gyroscopic forces generated by the

wheels, which improves turning and makes it easier to change direction, and

also reduces pitch during braking and acceleration.

Ducati first implemented

the counter-rotating crankshaft on the 2015 Desmosedici MotoGP racebike, the

first MotoGP bike Gigi Dall’Inga was in charge of building after he left Aprilia and joined Ducati

in 2013. Reversing the crankshaft rotation helped fix some of the handling

problems Ducati riders had experienced with the Desmosedici up until then.

Reversing the rotation of

the crankshaft requires adding a jackshaft to allow the crank to spin backwards

while still propelling the bike forward via the transmission, countershaft, and

final drive. The jackshaft system adds weight and friction, which takes away

some horsepower, but the handling benefits are well worth the minor power

loss—and the V4 still has horsepower to spare.

As previously described,

the Desmosedici Stradale engine uses the same twin-pulse firing order as the

Desmosedici MotoGP racebike. This helps make the bike more tractable during

acceleration by allowing the rear tire

to recover traction between power pulses and gives the engine the power

characteristics of a V-Twin. To achieve the firing order they wanted in a

90-degree V-4, Ducati engineers offset the crank pins by 70 degrees.

(Above) The engine has a 21.1 cc combustion chamber and four valves per cylinder.

The Panigale V4 also uses

Ducati’s

Desmodromic mechanical valve-opening and valve-closing system, which maintains

accurate valve actuation and control with high-lift cams and high peak rpm. The

34 mm intake valves and the 27.5 mm exhaust valves are steel, for durability.

The Stradale engine has a claimed redline of 14,500 rpm in first through fifth

gears, and adds another 500 rpm in sixth gear, taking the redline to 15,000

rpm—and an extra 500 rpm in top gear can be a life-saver (or position improver)

in race trim. Think of it as working like overdrive, while allowing the gear

ratios from first to fifth to be shorter without losing top speed in sixth

gear.

Feeding the engine is a

pair of double-barrel 52 mm ride-by-wire Mikuni throttle bodies fitted with

variable-length velocity stacks (a.k.a. air funnels) and eight fuel injection

nozzles, four located within the throttle bodies (one for each cylinder) and

four overhead shower injectors (one above each velocity stack). Each cylinder

bank has its own ride-by-wire motor, which allows them to be operated

independently, the best way to implement strategies ranging from traction

control to engine braking. The variable-length velocity stacks switch from long

to short depending on rpm (it feels like about 11,000 rpm) and throttle

position. Of course the basic idea is long stacks are better for lower rpm

power, while shorter stacks are better for top-end power.

The Stradale engine has a

semi-dry sump to reduce mechanical losses created by crankcase pressure. The

Ducati still has an oil pan, but it’s bolted to the bottom of the gearbox, not

underneath the crankshaft. Like the crankcases, the oil pan is made of magnesium,

and it is separated internally from the spinning crankshaft. The oiling system

uses four pumps: One delivers the oil; one scavenges oil from the cylinder head

and returns it to the sump; and the other two scavenge oil from the crankcase,

below the pistons, where pressure builds up. The system reduces internal

pressure and the drag caused by running the cams and the crankshaft through

accumulated (or pooled) oil. The Panigale V4 uses a six-speed transmission (as

mentioned earlier) and a hydraulically activated, assist-and-slip wet clutch

designed to increase plate pressure under acceleration (to reduce slip) and

decrease plate pressure under deceleration (to reduce back-torque and wheel hop

entering corners). The clutch has 22 plates, including 11 drive plates and 11

driven plates.

It’s all bundled together in a nice and compact,

but slightly heavy, V4. The engine configuration and dimensions have an

enormous role in the overall packaging of a bike, which also affects the way a

motorcycle handles. Ducati’s V-4 Desmosedici Stradale engine is 28 mm shorter vertically and 38 mm

shorter from front to back when compared to the latest version of the Panigale

V-Twin engine, but adding a cylinder to each side increased the width by 43 mm

compared to its V-Twin predecessor. The smaller dimensions allowed the V4

engine to be rotated backwards 42 degrees from the plane of the crankshaft,

placing it in what the engineers say is the same, optimal position as used for

the Desmosedici GP racebike. The V4 engine weighs 134 pounds (64.9 kg), making

it just 4.8-pounds (2.2 kg) heavier than the V-Twin Supersquadro engine despite

having more parts.

The V4 is all about

packaging, and Ducati engineers took full advantage of what was possible—which

means the chassis is a big departure from previous models that used a tubular

steel trellis chassis. The Panigale has an aluminum-alloy main frame, and it is

basically a short version of a conventional twin-spar, cast aluminum-alloy

perimeter spar frame, but is designed to work with the engine as a stressed

member, and the swingarm pivots in the crankcases. The main frame casting

incorporates a large headpiece and two sets of upper and lower spars, which

attach to each side of the engine. The main frame weighs 9.2 pounds (4.2 kg)

and gave Ducati engineers the ability to better tune the flex characteristics

of the chassis; the torsional (twist) rigidity and lateral (side to side)

rigidity of the frame can be tuned separately for the best balance between

stiffness and feel. The lower spars cradle the front cylinder, attaching to the

crankcases just below the cylinder, and the upper spar runs across the engine,

attaching to the rear cylinder bank using brackets. A magnesium subframe, which

weighs 4.2 pounds (1.9 kg), attaches to the top of the main frame and also

bolts to the rear cylinder bank at the bottom, forming a direct link from the

front to the rear of the bike.

Rake is 24.5 degrees, which

when combined with a triple clamp offset of 30 mm, produces 100 mm (4.2 inches)

of trail.

The 16-liter aluminum-alloy

fuel tank helps reduce weight while helping to centralize mass and minimize the

effect fuel sloshing has on handling. The tank is mounted above the upper frame

spars, runs down and behind the rear cylinder bank, and over the swingarm

pivot, with the base integrated into the seat above the rear shock. The shock

mount is also attached to the back of the engine, and the Öhlins EC 2.0 TTX 36 shock works through a

linkage with a 9.2% progression ratio.

Rotating the engine

rearward enabled engineers to move the swingarm pivot farther forward, allowing

the rear swingarm to be lengthened to 23.6 inches (600 mm)—which is hovering

around MotoGP length—without increasing the wheelbase. Using a longer swingarm

helps increase braking stability and rear grip, while also reducing the bike’s tendency to wheelie.

Swingarm angle is average, sitting around 11.67 degrees. The claimed wheelbase is 57.8 Inches (1,469

mm).

The Panigale V4 S model

comes standard with electronically controlled Öhlins suspension front and rear. At the front

is a set of 43mm NIX30 road and track forks with titanium nitride (TiN)

coating. Taking care of the rear is a TTX36 shock. The Öhlins Smart EC 2 system on the Panigale V4 S

has a new Objective Based Tuning interface (OBTi) which allows the system to

react to specific events. The Smart EC system uses input from the IMU along

with brake pressure, throttle position, and wheel speed to calculate where the

bike is in the corner, then adjusts the suspension accordingly. The system has

five levels of adjustment (1 being softest and 5 being hardest) for three

sections of the corner broken down into Brake Support, Mid-Corner, and

Acceleration.

The Panigale V4 comes with

Brembo 330 mm (12.9-inch) front brake discs and lightweight Brembo Stylema

monoblock calipers. Also standard are three-spoke Marchesini forged aluminum

wheels, and the Panigale V4 rolls on new generation Pirelli Diablo Supercorsa

SP tires. Pirelli engineers increased the width of the 120/70-ZR17 front tire

to produce a slightly larger contact patch. Rear tire width was increased by 16

mm, which made the rear contact patch 4.5 mm wider at full lean, on the

shoulder of the tire.

Ducati has upgraded the

electronics package on the Panigale V4 through a series of evolutions of

previously existing rider aids—which explains the EVO designation now used on

several. The upgraded rider aids are centered on a Bosch 6D (6-axis) Inertial

Measurement Unit (IMU), which detects roll, pitch, and yaw and sends the

information to the ECU to execute the necessary strategies to help keep the

bike under control and doing what the rider wants it to do. The use of an IMU

has become the standard for advanced motorcycle electronics these days, so it’s somewhat old news, but

the Bosch 6D IMU system processes the motorcycle’s movement very, very quickly,

improving the execution because it takes less time to detect the conditions

that create the need for electronic intervention.

The rider aids built into

the Panigale V4 S include ABS Cornering Bosch EVO (ABS EVO); Ducati Traction

Control EVO (DTC EVO); Ducati Slide Control (DSC); Ducati Wheelie Control EVO

(DWC EVO); Ducati Power Launch (DPL); Ducati Quick Shift up/down EVO (DQS EVO);

Engine Brake Control EVO (EBC EVO); and Ducati Electronic Suspension EVO (DES

EVO).

The Panigale V4 S features

three riding modes: Street, Sport, and Race. Full power is available in each

mode, but the rate of throttle opening is limited in the Street and Sport

modes. Street Mode has much softer throttle and suspension mapping, with the

rider aid levels turned up. Sport Mode has a more aggressive throttle map,

slightly stiffer suspension settings, less intrusive rider aid settings, and

allows the ABS value to be changed. Of course Race Mode is the most aggressive

of all, giving the rider direct throttle application, stiffer suspension, and

the ability to change all the settings.

It can be hard to keep up

with an ever-growing list of rider aids and functionality. But hitting the high

points, big changes were made to the ABS system on the Panigale V4. The EVO

system now has a three-level cornering ABS function aimed at improving

racetrack performance without sacrificing safety on the open roads. Level 3 is

for riding on the street, while Level 2 and Level 1 are designed for aggressive

riding on the racetrack. Level 2 has an interesting feature that allows the

rider to lock the rear brake and back the bike in at 0-35 degrees of lean. (I’d say the functional

racer in me looks at setting Level 2 as being unnecessary, but hey, it’s cool, have fun!) Level

1 is where the biggest advancements have been made, because the cornering

function allows the rider to brake aggressively without automatically reducing

brake pressure (and braking power) as the bike is leaned in. In other words, it

allows the rider to trail-brake to the apex of the corner, but if they overdo

it, it will react to help keep the rider from trail-braking themselves onto the

ground. It takes some of the danger out of trail-braking, although the system

can’t save a

rider who grabs a huge handful of brake lever and instantly spikes the brake

pressure!

DTC EVO offers nine levels

(1-8, plus Off) of traction control, with Level 1 producing the lowest and

Level 8 producing the highest level of intervention. As with previous models,

spin conditions are detected using input from the wheel speed sensors,

throttle, and IMU, with intervention being accomplished using either the

throttle plates to control power on corner exit, or by removing spark for an

unexpected big slide since the throttle plates react too slowly to catch that.

The strategy has been revised to limit big power cuts by recalculating the

allowable amount of grip in each setting. Ducati also gave the system a new “Spin on Demand” feature in DTC levels 1

and 2, which in theory should allow a less-experienced rider to use wheelspin

to finish the corner.

New on the Panigale V4 is

the two-level Ducati Slide Control (DSC). This system relies on the IMU’s ability to detect Yaw,

or when the bike goes sideways from sliding, and reacts to keep it from going

over the edge and highsiding the rider. Other measurements used to calculate

intervention requirements are acceleration (Pitch), lean angle (Roll), and

wheel speeds. The system limits wheel torque though a combination of reducing

throttle plate angle, cutting spark, and cutting fuel delivery as needed to

allow the rear tire to be hung out while still driving forward. Keeping the

Panigale moving forward, Ducati Wheelie Control EVO (DWC EVO) has been revised

to limit wheelies without removing too much power on acceleration. The EVO

system’s new

settings allow some wheel lift during corner exits, but doesn’t let it get out of

control or excessively slow acceleration.

Also new for 2018 is Ducati

Power Launch (DPL), or launch control. The system fitted on the Panigale V4

works in conjunction with the DWC and has three settings, with Level 3 being

least aggressive and Level 1 being the most aggressive. The system turns off at

about 100 mph or when the rider clicks into third gear. A clutch protection

feature was built into the system, which limits the number of consecutive

starts, to keep the clutch from getting burned up.

The revised strategies for

the Engine Brake Control EVO (EBC EVO) take engine braking to the next level on

a production bike. Ducati’s system adjusts pre-set engine braking parameters depending on the

situation, which is mainly based on rear tire wear. The system has four

settings (1-3, plus Off), with Level 1 producing the most engine braking, while

Level 3 has more run-on. Like most strategies, the engine braking is controlled

by throttle opening. Ducati’s Quick Shifter EVO up/down (DQS EVO) also works in conjunction with the

EBC system on downshifts, helping engage the desired gear by providing the

optimum amount of blip and duration via the ride-by-wire throttle control.

The DTC, DSC, DWC, and EBC

functions can be adjusted on the fly (while riding) through the left handlebar

switch bank. The functions that can’t be adjusted on the fly can be accessed using

the left handlebar to toggle through the new, 5-inch TFT dash display. The dash

has a choice of Track Layout, which displays lap time, and Street Layout, which

displays road information. Both modes have an analog-look tech display with

digital gear indicator and speed displays.

Ducati will also offer a

lower-spec Panigale V4, which comes fitted with Showa BPF (Big Piston Front)

forks and a Sachs rear shock along with a set of five-spoke cast aluminum-alloy

wheels and a U.S. MSRP of $21,195.

An ultra-premium, limited

production version, the Panigale V4 Speciale, will also be available, with

1,500 units being built. The Speciale boasts a claimed 226 bhp and weighs in at

414 pounds (188 kg). It comes fitted with a titanium Akrapovic exhaust, revised

rider aid and throttle maps, a host of special carbon-fiber parts, and a

special tri-color paint scheme with a MSRP of $39,995.

The Panigale V4 S as tested

in Valencia for this article will come with a MSRP of $27,496 and should be

available before spring.

Editorial Note: This article was originally published in the March 2018 print issue of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology.