Editorial Note: This article was originally published in the May 2019 print issue of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology.

BIKE INTRO: 2020 BMW S1000RR

Estoril, Portugal

ALL POWER, ALL THE TIME

By Chris Ulrich

I roll on the throttle and

load the pegs as I push my body forward over the fuel tank of the BMW at the

exit of Estoril Circuit’s left-hand, 180-degree Turn Four. The front wheel

comes up slightly as the S1000RR rips up through the rpm on the way to Turn

Five, a slightly downhill, fast fifth-gear right-hander with an open exit. I

breathe the throttle to set the front suspension on entry, then get back on the

gas to drive through the corner, and the BMW lights up the rear wheel as I grab

fifth gear and accelerate down the straightaway toward Turn Six. The S1000RR

pulls hard as I wind out fifth gear until I get to the braking zone for Turn

Six, a slightly-downhill, long left-hand turn made famous when Dani Pedrosa

rammed Nicky Hayden during the 2006 MotoGP World Championship race here. But

there are no torpedo jobs on this day as I grab the front brakes and downshift

to second gear. I trail the brakes off as I turn in, releasing the brakes as I

get to full lean, then let the bike drift wide before rotating the BMW around

three quarters of the way through the corner, and clip the inside curb to open

up the exit. The rear wheel spins and the front wheel lifts as I accelerate out

of Turn Six.

I am now at the point where the track gets

really physical, with a long acceleration zone followed by a fast kink, a long

braking zone, then another long corner followed by an acceleration zone that

requires real effort to get through, but I wasn’t in the physical or mental red

zone despite the hot pace. For comparison, on the HP4 RACE in 2017, I had

started to feel some fatigue at this point on the track. It was then that I

realized that BMW engineers really have made the S1000RR easier to ride, and

have still gained performance.

—

The BMW S1000RR redefined

the 1000cc segment when it was introduced in 2009. In the company’s first fully-faired

inline four-cylinder sportbike, BMW engineers created a machine that raised the

performance bar for the category. Before BMW arrived, most 1000cc sportbikes

made less than 160 horsepower at the rear wheel, but the 2009 S1000RR put out

185+ horsepower at the rear wheel, and the arms race was on! The first edition

of the S1000RR had a powerful engine, handled on par with the rest of the

category, and had advanced electronics for the time. It delivered pure

performance but was hard to tame.

The S1000RR also boosted

BMW Motorrad’s public image. The German company now had a cutting-edge

high-performance flagship sportbike to demonstrate its engineering prowess,

sending the message that the company was no longer only about touring and

adventure bikes and opposed twins. BMW’s new machine has claimed a chunk of 1000cc

sportbike sales, too, the company selling 80,000 units worldwide since 2010,

despite a challenging overall motorcycle sales environment. The halo effect the

powerful bike has had on the rest of the model line is also evident, with BMW

marketeers giving the S1000RR credit for helping BMW Motorrad sales grow year

over year. In 2018 alone, BMW sold 165,000 motorcycles and scooters

worldwide.

(Above) Besides making much more power, the 2020 BMW S1000RR is also easier to ride fast at full-power settings on the racetrack, thanks to carefully engineered power delivery and chassis flex characteristics.

Record unit sales, a new

model launch, and a change to an upper management team that believes in racing

as an effective marketing tool also saw the company field an official factory

team in the 2019 Superbike World Championship. BMW’s desire to use the S1000RR

as a marketing tool to reinforce the brand’s high-performance credentials is stronger than

ever.

—

The goals when BMW officials

decided to build a new 2020 S1000RR were very clear. Create a bike that is

lighter, faster, and more powerful than anything in the segment. Build a

machine that creates a revolution of sorts, like the first S1000RR did. The

ground-up project took close to 300 BMW engineers 46 months to complete and the

results include 8.0 more horsepower, and 24 pounds less weight.

(Above) Because it’s easier to ride hard, the latest BMW doesn’t wear out the rider as quickly as the previous versions.

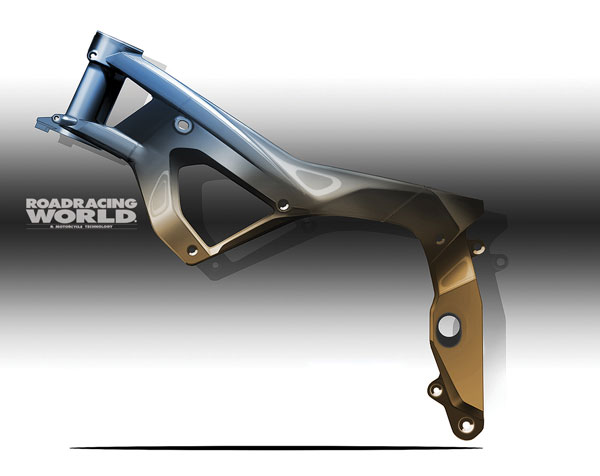

The 2020 model has a new

twin-spar aluminum frame tuned for optimum handling-enhancing flex (BMW

actually calls it “Flex Frame”) that uses the engine as a stressed member.

The swingarm is effectively longer, the engine is all-new, and a new, more

refined electronics package is easier to adjust and more effective on the

racetrack. So yeah, the new BMW S1000RR

is set to redefine the segment again, with three models, including the base

version, a Race Package version, and an M Package version. The hopped-up M

Package replaces the HP RACE and aligns the brand’s performance motorcycle marketing with the BMW

auto division’s

high-performance M-labeled model variants. The 2020 S1000RR is the

best-balanced, most powerful and most advanced four-cylinder streetbike in the

company’s

history. What it really all means is that the bike makes more power, and the

handling has finally caught up to the power.

—

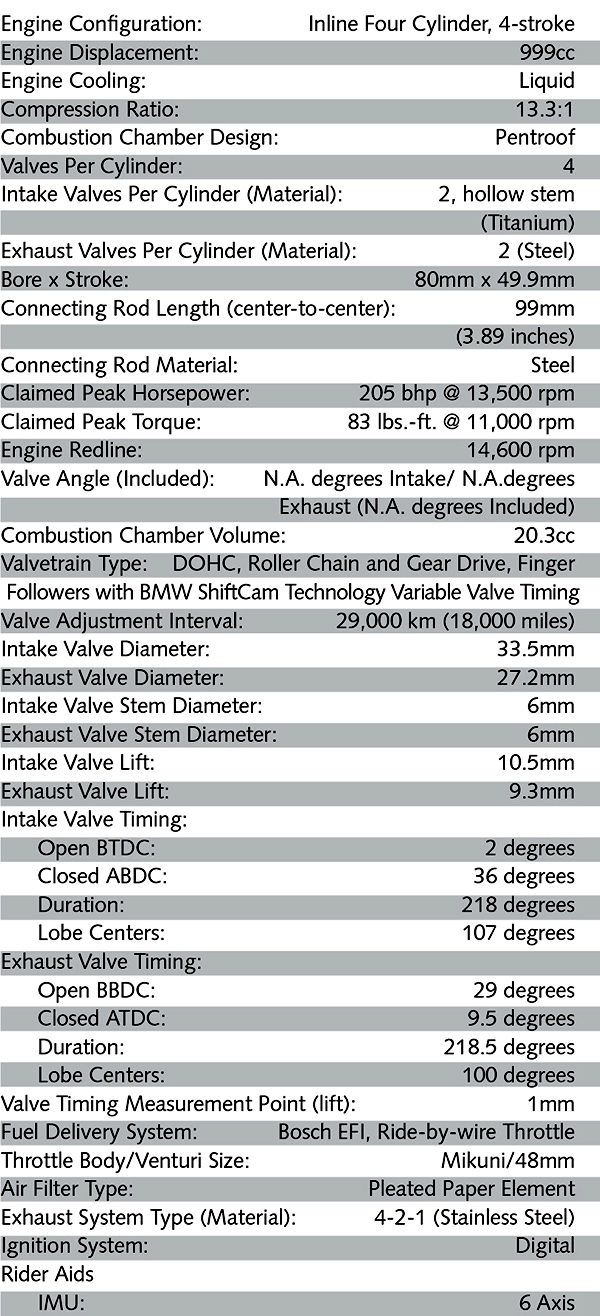

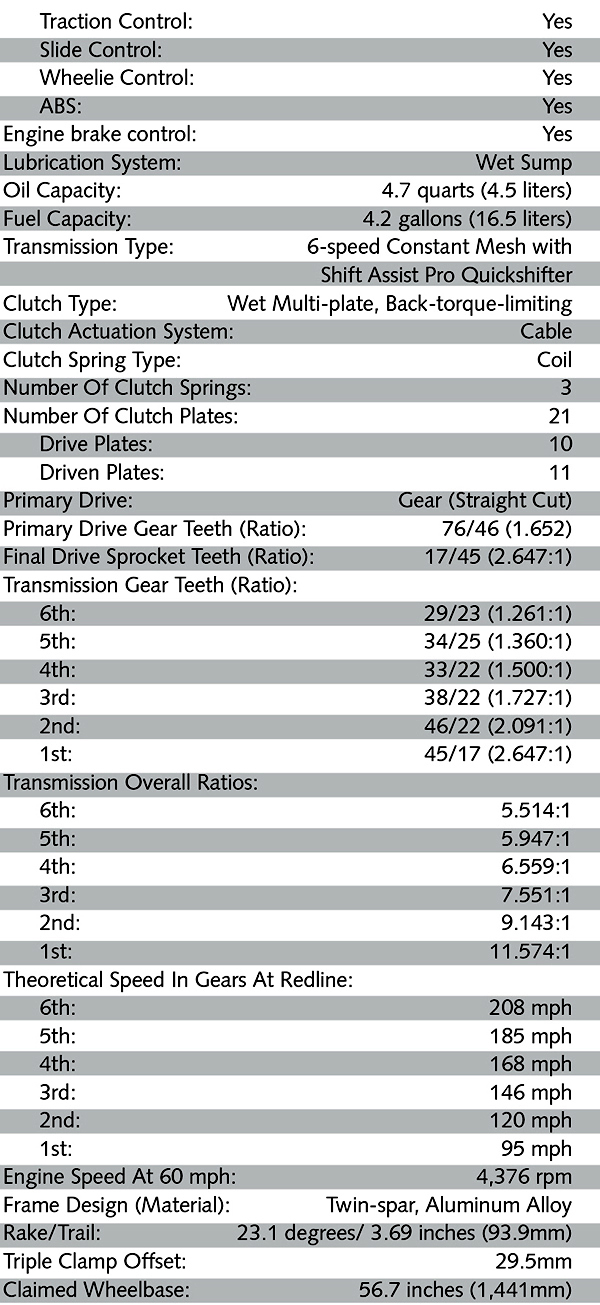

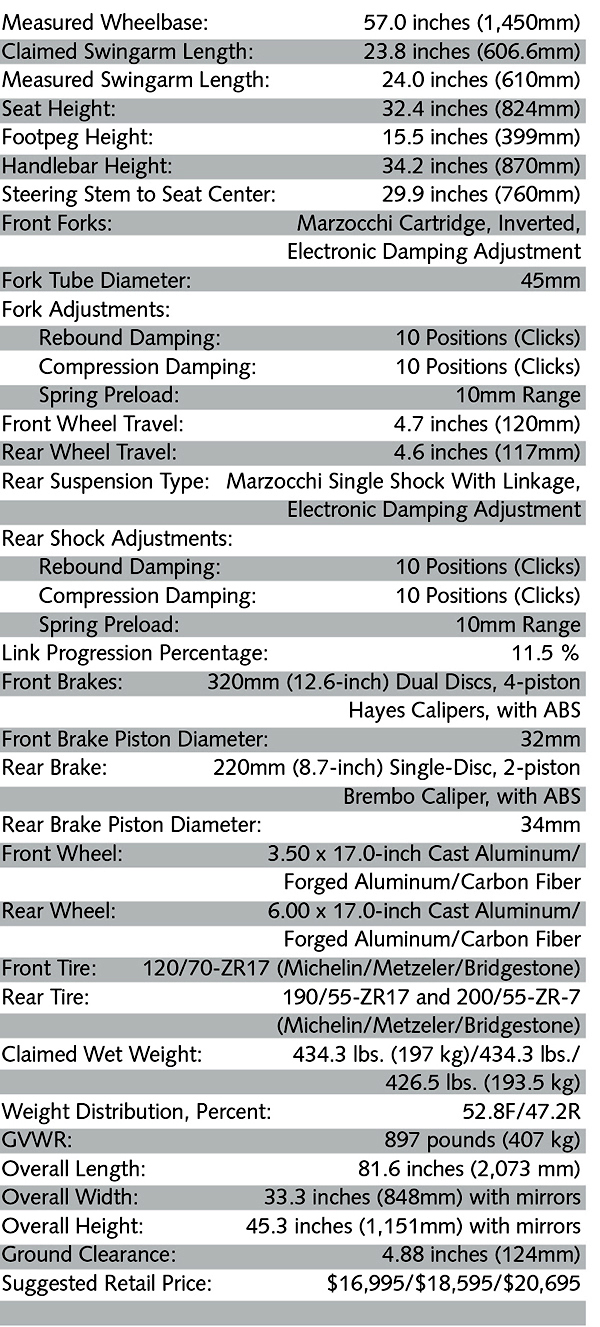

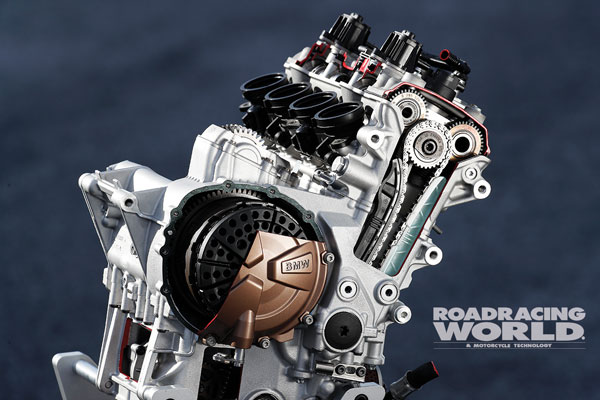

Because the S1000RR has

been all about power from the start, I’ll start the tech briefing with the powerplant.

It is an all-new 999cc DOHC Inline Four with a bore and stroke of 80mm x

49.7mm, a 13.3:1 compression ratio, and an advanced variable valve timing

system. The new engine is 8.8 pounds lighter, 12mm narrower, shorter, and more

powerful than the previous version’s engine, putting out a claimed 205 bhp at

13,500 rpm and 83.3 lbs.-ft. of torque at 11,000 rpm. More impressive is that

the S1000RR engine makes 73 lbs.-ft. of torque from 4,500 rpm and builds all

the way up to the 14,600 rpm redline.

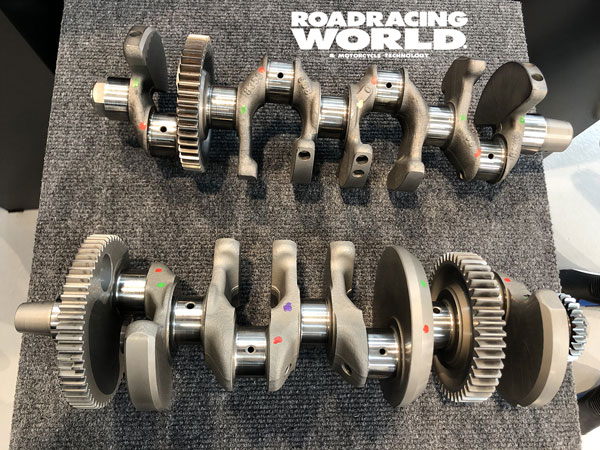

The weight reduction in the

engine was helped by shaving 3.5 pounds off the crankshaft, which allows the

engine to rev quicker during acceleration while also helping braking and

turning characteristics due to a reduction in centrifugal force. The connecting

rods are also slightly shorter center-to-center, going from 103mm to 99mm.

(Above) The latest S1000RR has a more compact and much lighter crankshaft, without sacrificing power delivery.

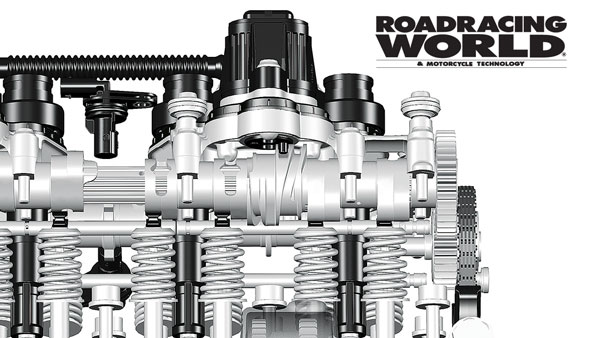

BMW engineers wanted to

create an engine with increased top-end power along with more low-end and

mid-range power, but those are normally opposing tuning goals and it’s usually impossible to

have the best of both—unless the valve timing changes midway through the rpm

range. Enter BMW ShiftCam Technology, which changes intake cam timing and lift

on the fly. The system uses servo motors that can only be controlled by BMW’s

Bosch ECU to drop pins into a channel on the intake cam, which moves paired

low-lift/short-duration and high-lift/long-duration lobes controlling each set

of intake valves. Below 9,000 rpm, the

camshaft opens the intake valves with the low-lift/short-duration lobes to

produce better low-end and mid-range power, and above 9,000 rpm the camshaft

opens the intake valves with the adjacent high-lift/long-duration lobes for

better top-end power.

(Above) The Shift-Cam system uses paired low-lift/shorter-duration and high-lift/longer-duration cam lobes, which slide into position over the finger followers depending upon engine rpm, shifting at 9,000 rpm.

The intake port shape has

been changed to work with the ShiftCam system. The head has four valves per

cylinder, titanium intake valves with the center of each stem bored out to

reduce weight, while the exhaust valves are made out of steel. The valves are

actuated by short finger-follower rocker arms that are plated with DLC (Diamond

Like Coating) and weigh 8-grams per unit, which makes them 25% lighter than the

rockers used on the previous model. The lighter weight valve train also allows

the safe rev limit to be increased by 400 rpm to 14,600 rpm. The engine

breathes through a set of four 48mm dual-injector throttle bodies with variable

intake tract length—the air-funnels (velocity stacks) change from long (for

better mid-range) to short (for better top-end) at 11,700 rpm.

The stainless steel exhaust

system contains two-three way catalytic converters. The mid-pipe and silencer

are shorter to increase performance and improve the sound, and the system is

2.8 pounds lighter thanks to the exhaust tube thickness being reduced from

0.8mm to 0.5mm.

(Above) The S1000RR engine uses a link-plate chain to drive the cams through a central gear.

The engine is tilted

forward at a 32-degree angle; using the engine as a load-bearing element

allowed engineers to reduce the new twin-spar frame’s weight by 2.8 pounds. The

geometry has also been changed, with rake reduced to 23.1 degrees which, when

combined with a triple clamp offset of 29.5mm, reduces the trail by 2.6mm to

93.9mm. Overall frame width at the base of the fuel tank has been slimmed down

by between 13mm and 30mm, depending on where it is measured. This might not be

a detail many people understand or pay attention to, but the center point of

the bike is where the rider meets the fuel tank and establishes their base.

Having the width right is important to allow the correct amount of support for

the legs to reduce fatigue, but not so much that is hinders movement. The

previous versions of the S1000RR were too wide in this area.

(Above) BMW has caught up in chassis performance with its “Flex Frame.”

The new chassis also

features a works-style cast-aluminum-alloy underslung swingarm that is just over

half a pound lighter than the previous model’s swingarm. Measured from the pivot to the

axle, the swingarm is 610mm long, which is the same as the previous model’s swingarm, but there is

an additional 35mm of chain adjustment left to actually increase the effective

swingarm length. Three options for swingarm pivot position adjustment are also

available: Stock, +2mm or -2mm. The swingarm downslope angle in the stock

position sits at 12.54 degrees, which is about optimal for the balance between

grip and linear slide characteristics.

(Above) The swingarm also has engineered flex.

BMW has switched to an

electronically controlled Marzocchi rear shock with a 46mm piston. The shock is

now mounted vertically and moved to minimize its exposure to radiant heat from

the engine. Changes to suspension linkage allow the rear spring rate to be

reduced from a 9.5 Nm to a 6.0 Nm, and the motion ratio for the rear shock

linkage went from 1.900:1 to 1.673:1 with a progression of 11.5 degrees. What

this means in the real world is more rear grip and longer tire life.

A set of electronically

controlled 45mm inverted Marzocchi cartridge front forks replace the 46mm Sachs

units used on the previous model. Like with the rest of the bike, the aim for

the front fork change was to increase feel reaching the rider without sacrificing

the balance of the bike. Reducing the

slider diameter is a good way to do that.

Suspension action front and

rear is controlled by BMW’s Dynamic Damping Control (DDC) system. The Marzzochi

version of DDC uses a conventional piston that has shims to control the damping

force based on the Riding Mode Selected. BMW engineers switched to a more

conventional suspension set up to give the S1000RR a more natural feeling on

the road and racetrack. There are four DDC settings available on the standard

bike, and each setting coincides with a Riding mode. In the standard Rain,

Road, Dynamic, and Race Modes the DDC is semi-active—reacting to suspension

movement and rate of change by increasing or reducing damping within a pre-set

range that can’t

be adjusted. Dynamic Mode gives more support and Race Mode gives the most

support. Full adjustment of the suspension settings is available in the Riding

Mode Pro, which is sold as an ECU upgrade. The semi-active feature is turned

off in the Pro modes; damping changes are still made through the DDC function

in the dash, but the system is designed to do nothing automatically in that

mode. The way BMW engineers describe computer interaction between the modes is

simple: Rain and Road Modes are 90% DDC and 10% conventional, while the Race

track settings are 100% conventional. Again, the aim is to give the rider a

more natural feeling while also allowing easy adjustment of suspension

settings.

(Above) Making power and also meeting emissions regulations requires lots of exhaust system volume, which BMW engineers placed underneath the engine to keep the muffler relatively small.

As with all modern 1000cc

sportbikes, the S1000RR comes with an advanced electronics suite with an

ever-growing list of capabilities. The 2020 version seems to be the

least-complicated, yet most-advanced version yet. All strategies are based on

measurements taken from a six-axis Bosch Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU). The

base ECU setting comes with the four Standard Riding Modes: Rain, Road,

Dynamic, and Race. Each riding mode has pre-set settings for throttle response,

torque maps, ABS, DDC, engine braking, Dynamic Brake Control, and wheelie

control. As before, traction control can be adjusted in the standard mode, with

15 levels of TC intervention—stock, stock +7, stock -7, and off. There are also

pre-set display options for the 6.5-inch TFT dash.

(Above) Race Pro electronics on the Race Package and M Package models include three settings, each with pre-set parameters. It’s an available $250 option on the standard model.

Additional functionality is

available by upgrading the ECU software to unlock the Pro Modes, which include

three setting options that can be customized to suit the rider’s preferences.

The software upgrades are included with the Race Package and M Package or can

be purchased individually for $250.

There are three

customizable Pro Modes: Pro Mode 1, Pro Mode 2, and Pro Mode 3, each setting

having a subset of adjustment that is customizable. For example, there are 15

levels of traction control available in each riding mode within Pro Mode. Other

rider aids that tended to confuse riders by providing too much adjustability—for example, Engine

Braking and Wheelie Control—now have three levels of adjustment. Traction

control can be changed on the fly, but all other settings, including the mode,

cannot.

BMW fans will notice that

the new Bimmer has a symmetrical front fairing; the previous asymmetrical

headlight version was created with styling in mind, but the main reason behind

the look was to reduce weight. Separating the low and high beam lights allowed

engineers to reduce the weight of the headlight package, but now, that’s not necessary thanks to

advancements in LED lighting technology. The 2020 model has a sleek,

symmetrical, aerodynamic upper fairing.

Cast aluminum wheels come

fitted on the base model, while the Race Package gets forged aluminum wheels,

and the M Package bike comes equipped with a set of lightweight carbon-fiber

wheels. The braking components have been changed, and all three versions come with American-made Hayes front brake

calipers with 32mm pistons and a Nissan radial master cylinder. Front disc

diameter remains 320mm. And for the first time, BMW is offering the S1000RR

with Bridgestone S21 DOT-labeled tires as original equipment.

The base model is available

for $16,995, the Race Package adds $1,600, while the M Package will cost an

additional $3,700. BMW is expecting 2020 S1000RRs to available in showroom

floors late in 2019.

—

The day of riding consisted

of five, 15-minute sessions for each rider/reporter. The press group started

the day on Bridgestone Battlax S21 DOT-labeled tires before moving on to

Battlax VO2 slicks in the afternoon. We all rode S1000RR models with the M

Package upgrade which is highlighted by carbon-fiber wheels and the Pro Mode

electronics package.

The first session of the

day was spent rolling around in Pro Mode 2 with the traction control turned up

to Level 3. It was a good opportunity for me to reacquaint myself with the

layout of Estoril while checking out the grip of the new pavement laid down in

the second half of 2018. The layout of Estoril is good for testing, combining

long braking zones and a good mix of slow, medium, and high-speed corners.

The new S1000RR made more

power than I expected and the power removal was much smoother than in previous

models—which demonstrates that BMW engineers worked really hard on the

ride-by-wire throttle maps. At full lean and through the acceleration zone, the

ECU removed power, but then smoothly fed the power back in when the bike was

straight up and down. My initial

impression of the ergonomics and chassis was positive. The bike turned in

better and was easier to transition than the previous model, and no doubt this

was helped by the carbon-fiber wheels

With the cobwebs blown out,

I upped my pace in the second session, but I left the traction control turned

up just to see how the S1000RR and Bridgestone S21s reacted as I went

quicker. A lot of power available at my

wrist combined with a street tire made for an entertaining session, but it also

showed how much the traction control strategies have improved since 2009. BMW

uses a two-stage approach to traction control; the first is what the engineers

described as slow, or pre-control, which removes power based on lean angle and

TC setting using the throttle plates. The second is by ignition cut, which is for

fast, unexpected events, like a sudden slide. Think of it as the Save Your Ass

(SYA) tool—and I used the SYA feature of the TC a few times on the S21 tires!

Anyway, BMW engineers improved the function of the traction control by placing

both pre-control TC and SYA TC on the same channel in the ECU. Both systems get

the same feedback from sensors, allowing them to work in unison when

intervening.

On corner entry the ABS was

busier than the traction control; I had a few more front-end tucks than I was

comfortable with as I went quicker; after four big moments, I backed off the

pace and decided to wait for the slicks before I pushed any harder.

The real testing started

when the Bridgestone V02 slicks were fitted onto the bike for the afternoon

sessions. As usual grip brings out the best (or worst) in a bike and the BMW

was no exception. I was able to get down to business with grippy slick tires on

the bike. I played with some traction control settings as the day went on, but

eventually ended up on TC -2 because it had the right ratio of spin-to-power

removal to allow me to turn better lap times around Estoril.

I really noticed the

changes to the ergonomics as I picked up the pace. The new fuel tank design

allowed me to lock in my outer leg and support myself during heavy braking,

which took pressure off my shoulders and forearms, while still allowing me to

move side-to-side without any hindrance. The seating position and seat height

also helped take pressure off my shoulders, while allowing me to be agile on

the bike. You see a theme here? BMW’s engineers paid close attention to the

dynamic position of the rider to limit fatigue. And it was apparent on-track at

Estoril.

The S1000RR engine has a

very linear power band that delivers tractable power—the whole point of

variable valve timing. The engine starts making good power as low as 4,000 rpm

and carries it until the ShiftCam switches to the top-end setting as engine

speed climbs past 9,000 rpm. The throttle connection from first touch all the

way through the acceleration zone is really good; the power is there, so you

always know where you are, but it isn’t so much that the bike is unmanageable.

Then it keeps pulling as the ShiftCam transitions to top-end power settings.

Another power boost comes in when the variable-length stacks open to their

top-end phase as the engine passes through 11,700 rpm. There isn’t any big,

defined hit along the way; the bike just keeps making more power and ripping

through the rpm gear after gear! The power never goes away!

There’s something about ABS and ripping around a

racetrack that does not compute, and while the new BMW’s ABS is better on-track than the previous

models, it isn’t

perfect—and nobody else’s is, either. It still starts to fade (or intervene) after 3-4 laps of

hard riding, but it feels like fade. But unlike with the previous models, the

system then remains consistent and predictable. (Sometimes the lever would

unexpectedly come in to the handlebar on the previous models.)

The front suspension

performance during braking was good, especially in the long braking zone coming

off the front straight into Turn One; the forks had plenty of support to allow

me to brake later as I went from sixth to second gear, but still had good feel

that allowed me to trail the brakes deep into the corner. The biggest

improvement from Marzocchi DDC forks is the feel deep in the stroke; BMW engineers

have managed to find the right damping setting and oil level to improve front

feel from corner entry all the way into the middle of the corner.

The rear suspension worked

well on corner exit through the acceleration zone. I added some support to the

rear by changing the DDC setting to make the bike finish the corner a little

better. The feel from first touch of the throttle was good, and drive grip was

also decent, as were the slide characteristics of the rear during hard

acceleration.

I experimented with some of

the other rider aids as the day went on, starting with the engine braking

control. I tried moving the engine braking setting from the mid-range Level 2

to the least amount of intervention, Level 1, but then struggled to slow the

bike down without using more brake pressure than I wanted and I started missing

apexes all over the track. So I returned to the pits and put the setting back

to Level 2.

The middle wheelie control

setting also functioned well, allowing the S1000RR to carry the front wheel

during acceleration, but not let things get out of control or slow the bike

down. That demonstrates that BMW engineers have

really done a good job with the most recent ECU and electronics

development.

—

By the end of the day, I’d

done all five of my 15-minute sessions including a lot of hard riding on the

2020 S1000RR and I wasn’t sore. In fact, I was barely tired, which says a lot

about the rideability of the bike. In 2009 BMW unleashed a high-powered weapon

that forced every manufacturer in the segment to step up their performance.

They did, and they brought weapons that were just as fast, but easier to ride

for longer periods of time. Now BMW has responded and made one of the most

brutal 1000cc sportbikes on the market also one of the easiest sportbikes to

ride without sacrificing any of the pure performance we’ve come to expect from

the Bavarian company’s engineers.

It’s really good!

SPECIFICATIONS: 2020 BMW S1000RR Standard/Race Package/M Package