Part 1 of a series, reprinted from the April 2011 edition of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology Magazine. Copyright 2011, 2015, 2020, 2024. All rights reserved. www.roadracingworld.com

RANDY MAMOLA, NIALL MACKENZIE AND GUY MARTIN’S DAD GIVE US THE INSIDE LINE ON HOW TO BE A RACER’S DAD

By Mat Oxley, (April 2011)

MotoGP, Moto2 and World Superbike grids are full of them—racing sons of racing fathers. From Valentino Rossi and Casey Stoner to Stefan Bradl and Leon Haslam, the motorcycle racing world is ruled by riders who have had been bred for speed, via both nature and nurture.

Gone are the days when youngsters instinctively rebelled against what their parents did; now we’ve gone back to the old, old times when the son of the candlestick maker became a candlestick maker.

And there’s no one better to dispense advice on bringing up your own kid to be a hard-core, race-winning motorcycle racer than a hardcore, race-winning motorcycle racer. Forget the harrowing tales of five-year-olds tumbling from their motocross bikes, lying sobbing in the mud while their dads scream at them to “man up” and get back onboard; these men will tell you how to be a nice and successful racer’s dad.

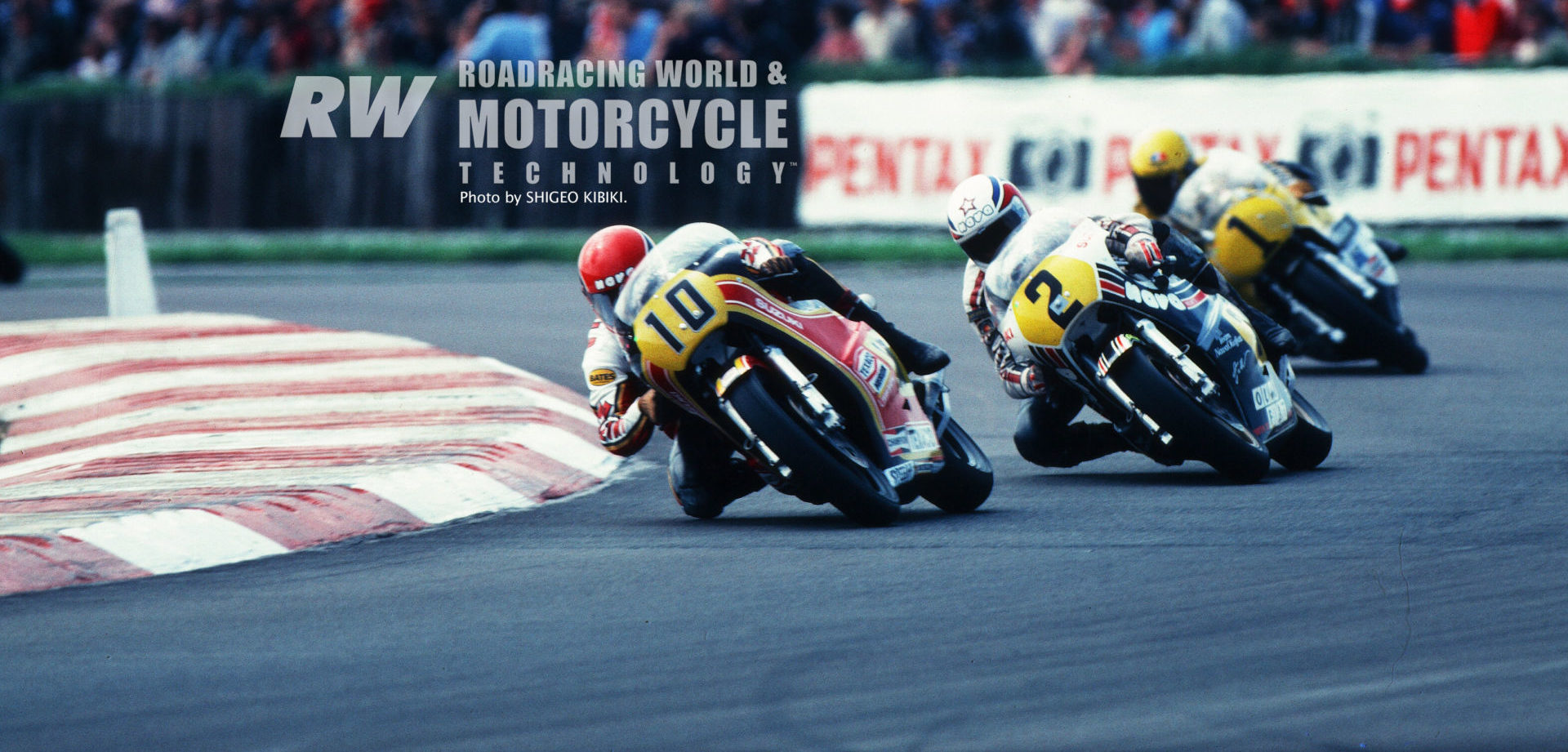

Randy Mamola is the most successful GP racer never to have won the premier World Championship. Mamola won 13 500cc Grand Prix races for Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha, and his son Dakota now races in the British 125cc Championship.

Niall Mackenzie scored 500cc Grand Prix podium finishes alongside Kevin Schwantz, Wayne Rainey and Mick Doohan. These days he looks after sons Taylor and Tarran who also race in the British 125cc Championship. Taylor is already winning British Championship races.

Former TT rider Ian Martin is dad of real roads maverick Guy Martin. And 125cc GP and Moto2 winner Stefan Bradl is son of 1991 250cc World Championship runner-up (and five-time GP winner) Helmut Bradl.

“The Hardest Thing About Being A Racer’s Father Is The Guilt”

Multiple GP winner RANDY MAMOLA has a six-point plan for racer dad success.

- Stress Education and Discipline

“Whatever your children want to do in life, you get behind them. But it’s got to be in the kid’s heart, they’ve got to really want to do it. That’s the same across the board, learning at school and so on. What my wife and I impress on Dakota is that education is of the utmost importance. With racing, training and school work he’s got a lot going on, a lot of late nights and early mornings. He’s a typical kid—every now and again he falls out of line—so we discipline him, like we ban him from riding his scooter.”

2. Don’t Pressure Them

“The hardest thing about being a racer’s father and trying to get stuff over to your kids is the guilt. You ask them to do something, you give them guidance, something happens and they crash. So I try not to put pressure on Dakota. I have the same concerns as any parent, but I’m the same at a GP. Every time those MotoGP guys go out and do their battles, I say a small prayer for them.”

3. Racing Isn’t Work, It’s An Adventure

“My childhood ended when I started racing at 12. I didn’t have girlfriends and all that because I was always on the road and racing. That’s the life of a sports person—it just absorbs you and there’s nothing you can do about it. When I raced, it wasn’t work, it was an adventure. When I was a kid I wanted to be a drummer, then I rode a motorcycle and it was the trickest thing ever. Everyone reading this knows that when they first got on a motorcycle it changed their life forever.”

4. Disassociate Your Relationship

“As an ex-racer and a father, I know too much, which can go against my son, but all in all, it’s definitely going to go for him. Its sometimes more frustrating to get something across to your own blood. If you disassociate that, you can probably communicate better. When I talk to other kids I get through to them easier than I can with Dakota, because we’re too close. I’m his father, so he sees me first as someone who disciplines him.”

5. If You Argue, Apologize

“There’s times when Dakota and I get upset with each other, that’s normal—he’s a kid under pressure and I’m his dad. As a kid, pressure is want. It’s not pressure in a bad way, it’s pressure in taking you to the next level. If I’m too hard on Dakota I apologize—I tell him it’s only because I want him to do certain things and I can see he could do them if he just did this or that. Also, I’m learning to be a father handling the pressures he’s going through which I once went through.”

6. Give Them An Open Mind

“I walk tracks with Dakota. We stand at a corner and I ask him, ‘What are you doing here?’ He says he’s doing this, so I say, ‘What about doing that?’ What’s really rewarding is when he goes, ‘Wow, that works!’ But you’ve got to keep it very open. You say what works for me may not work for you, but what I want you to see is that there are always different solutions—always keep an open mind.”

Postscript: When this is written in early 2011, Dakota is currently waiting for a serious left shoulder injury to improve. The injury, which he first sustained in 2007 but has since led to multiple dislocations, includes nerve and muscle damage which means he is unlikely to ride again until late 2011 at the earliest. “We’ve had offers from teams to race in the UK and in Spain, but we’ve had to put it all on hold to give his body a chance to recover,” says Randy Mamola.

“I Can Give Them A Map Of The Best Way To Approach Racing”

Former British Champion NIALL MACKENZIE has a plan for his two kids.

“It’s great for any family to do stuff together. I don’t think it’s too important to be best mates with your kids, but my relationship with my kids involves a lot of respect and a lot of fun. The best thing is that they desperately want to go racing, which is a great lever for doing school work and behaving well.

“Apart from having fun on bikes there are a lot of life lessons in racing. When they are young and innocent they think everyone in the paddock is wonderful, but they soon realize not everyone is what they seem.

“They don’t really believe you when you tell them stuff, so when they’re having a really bad day you tell them it could all turn around tomorrow and it quite often does. When that happens you remind them what you said, so the next time they know that things can turn around.

“You do see parents who expect their kids to be out there winning. It may sound a bit strange, but up to now winning hasn’t been the thing we’ve been working towards. We just work towards them getting better. It’s dangerous to push them to win in the first few seasons; so much can go wrong. I’ve probably held them back more than given them a push.

“I’ve made my kids aware that there’s some mad parents out there and there’s parents who don’t send their kids to school as much as they should—maybe they know their kid’s going to be the next Rossi…

“I really believe I’ve got a good template. I can give them a map of the best way to approach it; not so much on riding, but on having a plan: Being organized, being fit, keeping the risks to a minimum, learning to be a racer step-by-step, rather than trying to do it all in one weekend.

“My approach is to give them little bits of information, rather than bombard them with too much. The aim is always to make progress, whether it’s a better lap time or smoother riding. Always small goals and small steps.

“Our first priority is safety. If we leave on Sunday night and everyone is in one piece, that’s a successful weekend. As a parent you are programmed to protect them, not to put them in vulnerable positions, so in a way it does feel all wrong.

“They’ve had a few knocks. The worst was seeing this older guy on a 600 make a stupid pass and wipe out Taylor in testing. He was only 15 and that was horrendous seeing a hairy-arsed adult do something to your child. I keep reminding them that it’s dangerous: You don’t have to do this, if you feel scared you’ve got to walk away. I don’t push them because I couldn’t live with the consequences if they got hurt.

“I drum it into them: Give it everything you’ve got and try to enjoy it along the way. They definitely dream of making it to MotoGP, but they are realistic. They know that if this doesn’t work out that the rest of life isn’t a disaster. They’ve got skills and talents I never had at their age, so I make that clear—they can do anything they want.”

“I Thought Blooming Heck, This Isn’t Looking Good”

Ex-TT racer IAN MARTIN’S son Guy is addicted to the most dangerous form of bike racing, on public-road circuits. How does a dad deal with that?

“It was the laptop job what got Guy started on the roads. He got a 10-second penalty for cutting the chicane at Rockingham in 2002, that’s when he had that do with the official’s laptop. ‘Course they took his license off him.

“I said, ‘You better have a rethink, boy, knuckle under and do what you’re told.’ Guy’s a bit highly strung… from his mother’s side! He said, ‘We’ll have to get an Irish license and go road racing.’ I took him ’round Scarborough (a street circuit in northern Britain) in me van, showed him the way ’round and he said, ‘Aye, I think I could get into this.’ He did some Irish short-circuit meetings and then the Newcomers (race) at the Ulster GP at Dundrod—that was unbelievable—the Newcomers record was 112 mph and he put it up to 118.

“I don’t think I’ve ever done a TT lap with him. The first year his biggest thing was the David Jefferies onboard DVD, so he was totally focused as soon as he went. Having done the roads meself I know the buzz you get. I don’t think there’s a buzz anywhere like going down Glencutchery Road. I know what the lad’s feeling, so you can’t take that away from him. I’m 100% behind him.

“It’s this adrenaline thing. He says you’ve got to do things that take you to the edge and you don’t get that on short circuits. He’s a bit of a maverick. Even at work, he doesn’t conform to the norm. I was one of them fathers who let the mother do all the keeping him right. I just told him behave yourself and that was near enough for me. He was good at school, not outstanding. His maternal granddad was Latvian; had to fight for the Germans in World War II, so that may be the oddball bit.

“I’m not nervous at all. The only time I was really worried—apart from his big crash this year (2010), of course, when I was at home—was when I pit-boarded for him at Ballacraine a few years back. He’d gone through and next minute the red flags come out. Next thing a fire engine comes ’round the corner. I thought, `Blooming heck, this isn’t looking good.’ But it wasn’t Guy. Big sigh of relief.”

“When You Are Young And Things Go Bad, Your Head Is Destroyed”

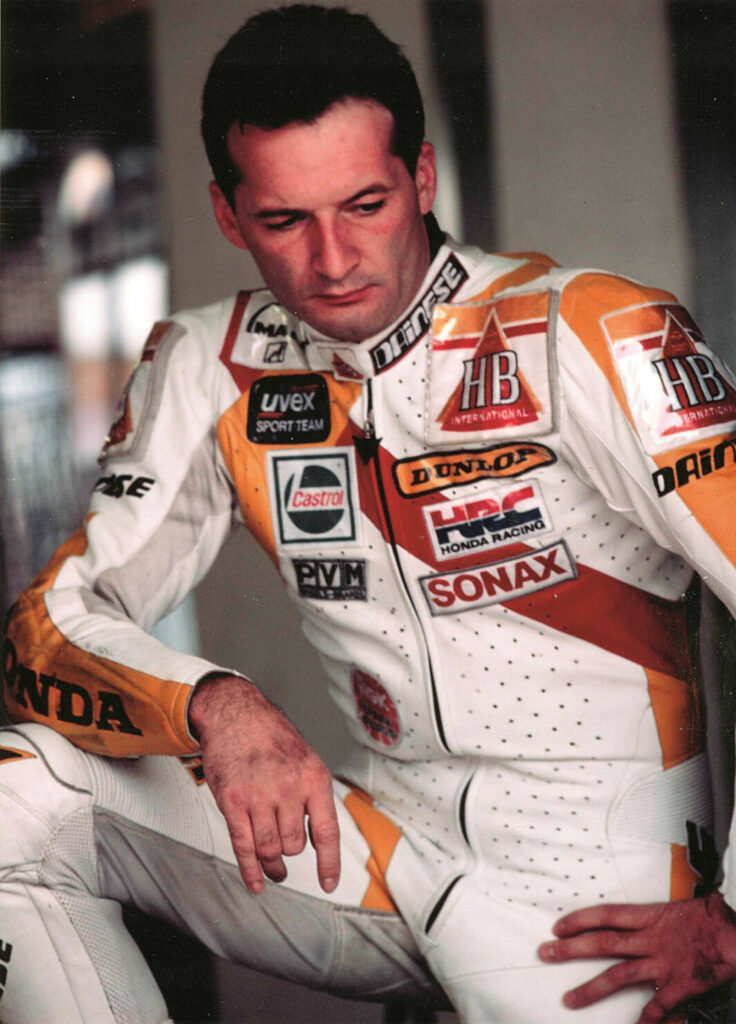

STEFAN BRADL tells us what it’s like being the GP-winning son of a GP-winning dad.

“I started racing because I was inspired by watching videos of my father. I started riding around the garden when I was four, just for fun. I only thought about racing when I was 12. My parents weren’t happy, but they said, ‘OK, we don’t want to stop you, we’ll give you a chance and if you’ve got talent we will help you.’

“When I started it was very important to have my father by my side because I knew nothing—he taught me about lines. settings. tires, more or less everything. He just gave me tips. He would only say, ‘Try this.’ He never said, ‘Do this.’ He never gave me pressure and that was very important.

“Sure, I made many mistakes and my father lost a lot of hair because of me! I always wanted to go my way, but I followed his tips when possible. He gives me less advice now, though sometimes he has an idea and I say, ‘Why not, let’s try it.’

“The biggest thing, when you are young, is that when things go bad your head is destroyed, so you need somebody by your side. Everyone needs somebody to be with at the track, like Valentino (Rossi) is always with Uccio. To be alone at the track is not OK, you need someone who can take you out of racing, because being focused on racing 24/7 is bad.

“I had a bad accident in Malaysia when I was 16 and my leg was shattered. I was f—— happy my parents were there. But sometimes being with your dad 24 hours a day can be too much. We do have arguments about racing—my mother always in middle—sometimes big ones. The biggest of our relationship was last year when I wanted to go to Moto2. My father wanted me to stay in 125s another year, but I wanted to change classes. Eventually, I hope to be in MotoGP.”

Check back tomorrow for the next installment of Taking Kids Racing.