The following article was originally featured in the September 2018 issue of Roadracing World & Motorcycle Technology magazine. To read more articles like this please subscribe to Roadracing World.

MotoGP Legend Randy Mamola

By Michael Gougis

One could hardly blame

Randy Mamola if, now and again, he wondered what might have been. There is no

title in motorcycle road racing more prestigious than the 500cc/MotoGP World

Championship, and Mamola finished second four times—in 1980, 1981, 1984, and

1987.

But earlier this season

Mamola earned an award that puts him in even more rarefied company. The San

Jose, California, native was named a MotoGP Legend, one of 27 in the

organization’s Hall of Fame. It is easier to win a World Championship than it

is to make it into the MotoGP Hall of Fame.

“It is a great honor,

not being a World Champion, but being able to be seen as someone recognizable

(at that level),” Mamola says. “I knew I was famous in the sport for

many things, my riding style, my work I do for the sport—but I think this

recognizes what I did outside the track, and what I do 26 years after I stopped

racing.

“I went online and

started punching in ‘legends,’ not only in our sport, I was trying to really

think about what a legend is. I know I adore my sport, I like most of the

people in it,” Mamola says, laughing, “and motorcycling is at the

forefront of what I do.”

Mamola earned his place as

a MotoGP Legend for what he did on the track, and for what he has done since

retiring from racing.

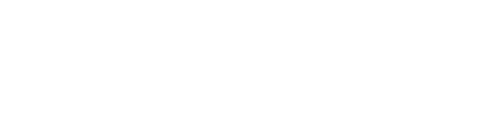

What he did on the pavement

was astounding: 13 Grand Prix wins and 57 podiums in the 1970s, 1980s, and

1990s. Mamola accomplished that while riding for four different manufacturers:

Suzuki, Honda, Yamaha, and Cagiva. At the height of his racing prowess, he was

a threat to beat the best riders ever to road race a motorcycle.

Mamola was second in his

fourth 500cc GP race, in 1979. Mamola scored his first win the following year,

in only his ninth 500cc GP race. In that race—the Belgian Grand Prix at

Zolder—he beat Marco Lucchinelli by more than 12 seconds and Kenny Roberts,

that year’s 500cc GP World Champion, by more than 31 seconds. Barry Sheene,

Eddie Lawson, Freddie Spencer, Wayne Gardner—Mamola raced and beat them all

during his premier-class career.

What he’s done since

retiring after the 1992 season demonstrated his dedication and his passion for

the sport of road racing and for motorcycling. He’s well-known for his charity

work as the co-founder of Riders For Health, the organization that provides

health care via motorcycle to remote areas of Africa, and with Two Wheels for

Life, the MotoGP charity that raises funds for Riders for Health.

He’s even more well-known

for his work in the road racing community. Since retiring, he’s served as a

racing columnist, a television commentator, and as a pilot for one of the most

terrifying vehicles imaginable. A 260-horsepower MotoGP machine is

intimidating, to say the least. Imagine one with a passenger seat and a passenger—often

someone who’s never been on a racebike—hurtling down the back straight at

Silverstone at 185 mph, and you start to get the idea…

Today, Mamola splits his

time between Northern California, where his elderly parents live, and the

Spanish city of Sant Pere de Ribes, near Barcelona. It’s a bit inland from the

shore, where there are fewer tourists, and adjacent to the town of Sitges,

where many racers from around the world made their European homes in the 1980s,

Mamola says.

But in a very real way, home

for Mamola is the next plane, the next airport, the next hotel. He estimates

that he no longer spends 200 nights a year living from a suitcase, but the

number of days he’s still traveling is not far off that number.

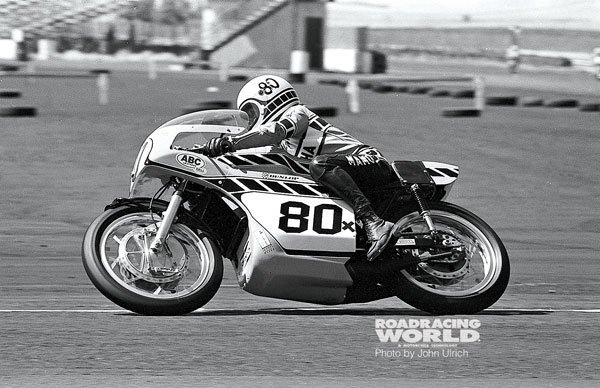

His duties with MotoGP as

the pilot of the two-up Ducati machine occupy most of his work time nowadays.

Mamola also is associated with Monster Energy, and he is at 14 Grand Prix races

a year minimum, and most often 15, depending on where the two-seater is slated

to show up. It is a job he’s been at for a very long time. Mamola says that

Kenny Roberts’ team built the first two-up GP bike, a 500cc Yamaha, all the way

back in the mid-1990s.

After retiring, Mamola did

a long stint with Eurosport as a commentator. After three-time 500cc GP World

Champion Wayne Rainey was injured, Rainey did some commentating, and one day,

while Rainey and Mamola both were working the microphones on a race, Mamola

says Rainey turned to him and said, “You’re really the one who should be

doing this.” Mamola did the Eurosport duties for nearly a decade.

Interestingly, for a guy

who’s spent so much of his time in Spain, Mamola now spends about two hours a

day learning to speak Spanish. That’s because of his latest gig as a television

commentator with the Spanish telecommunications company Movistar. His first

outing was at the MotoGP event at the Circuit of The Americas this year, and

it’s something that helps keep Mamola current and in the paddock.

And perhaps not

surprisingly for a rider with his fame and fan popularity, Mamola is in

demand on the classic racing and

exhibition circuit. He did the Goodwood Festival of Speed in England again this

year, and was one of the featured guests earlier this year at the Mike Pero

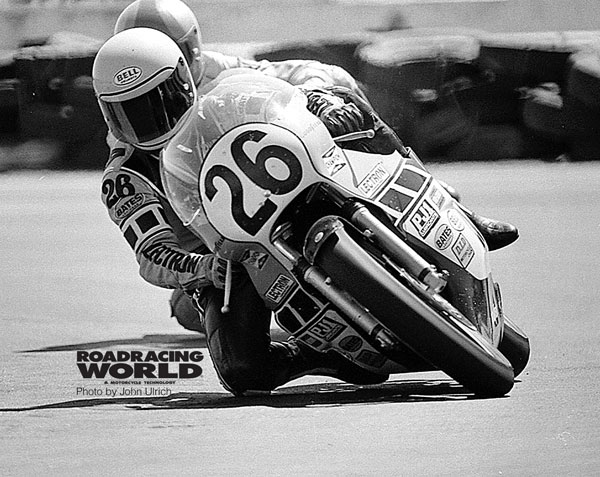

MotoFest in New Zealand. That one was special for him, as he got to ride one of

his 1980 Suzuki RG500 Grand Prix racebikes, one that was in “good

nick” as it had been fettled by former GP mechanics Mike Sinclair and

Jeremy Burgess.

It also makes Mamola one of

the very, very few human beings who have ridden a 500cc GP bike and a modern

MotoGP machine in 2018. At MotoFest, on the Hampton Downs International

Motorsport Park circuit, Mamola pushed the RG500 hard enough to impress former

Superbike World Championship star Aaron Slight, who was riding wingman to Mamola

as they circulated the track.

“Aaron said to me, ‘I

can’t believe how hard you’re riding that thing,'” Mamola says. “It

brought back such really good memories of how to ride a 500. It is so

responsive—remember that a MotoGP bike weighs about 80 pounds more than the

500s I used to ride. And I was always aware of how easy it was to have one of

those things get away from you.”

It’s a dramatic difference

to the two-up machine he rides, a Ducati Desmosedici with a 2012-spec engine,

the same one used during the Valentino Rossi era at Ducati, Mamola says.

“The bike is a testament to how the world has changed, the

technology,” Mamola says. “It revs to 16,200—we can rev it higher,

but why? It makes 260 horsepower. It’s a real toy. I friggin’ laugh every time

I get on it. It’s just awesome.”

One of the key differences

between riding the 500s and the MotoGP bikes is the level of fitness required

of someone who can push a MotoGP machine for a full Grand Prix distance, Mamola

says. One of the benefits of his status with Dorna is that he occasionally gets

to take VIPs out to vantage points that normal humans never get to visit, and

Mamola gets to describe to his guests what they are seeing from very, very

close up.

“You watch a MotoGP

machine come into a corner and you think there is no way they are going to be

able to brake hard enough to make the corner,” Mamola says, “and then

they do. You have to be so strong. You have to be so in tune with everything.

The physical conditioning you need is incredible.”

While he spends much of his

time in Europe, Mamola is a strong supporter and fan of U.S. road racing, and

looks back happily on his time racing in the U.S. “I got to visit with

(Mr. Editor) John Ulrich at COTA, and we’ve known each other for a very long

time. He’s always been a part of racing, and getting to know his son and Team

Hammer brought back really fond memories.”

When you take it all in,

the career that started in the AFM, the early years road racing in New Zealand,

the brief and impressive career in AMA 250cc competition before heading to the

Grand Prix circuits, the accomplishments there alone put Mamola among racing’s

elite. The work since simply justifies Mamola’s inclusion among the giants of

the sport.

And yet, Mamola remains a

down-to-earth character. His family makes sure his feet remain firmly on the

ground. Mamola remembers getting a message from Ignacio Sagnier from Dorna at

about 4:30 one morning. Mamola was in the U.S., and headed out to his car to

return the call without waking anybody else up, as his curiosity had gotten the

better of him.

“I called Ignacio,

asked him ‘What’s

up?’ He said,

‘This year,

for MotoGP Legends, they want to bring in you and Kork Ballington.’ It was super-nice

because Kork was one of the riders I looked up to. He was bloody fast in the

250cc and 350cc class when I first got involved.

“It was overwhelming

in a personal way. I didn’t really start to think about it until I’d hung up.

He said, ‘Let

it sink in, we’ll talk, we’ll put something together. We want to do it in

Texas.’ I

hung up and I went back inside.

“When my son got up,

and my friend was getting up to go to work, I kind of made a joke, ‘Well, you

guys, you’re looking at a Legend.’ And of course my son said, ‘Oh s—, now we

have to live with this!’”